Maureen, You are very welcome to my WRITERS CHAT series. Congratulations on your debut novel Limbo: A Kate Frances Mystery (Poolbeg Crimson: Dublin, 2022).

It’s a real page-turner of a thriller that reminds us of how far we’ve come in terms of equality and bodily autonomy but also how far the reality has still to go.

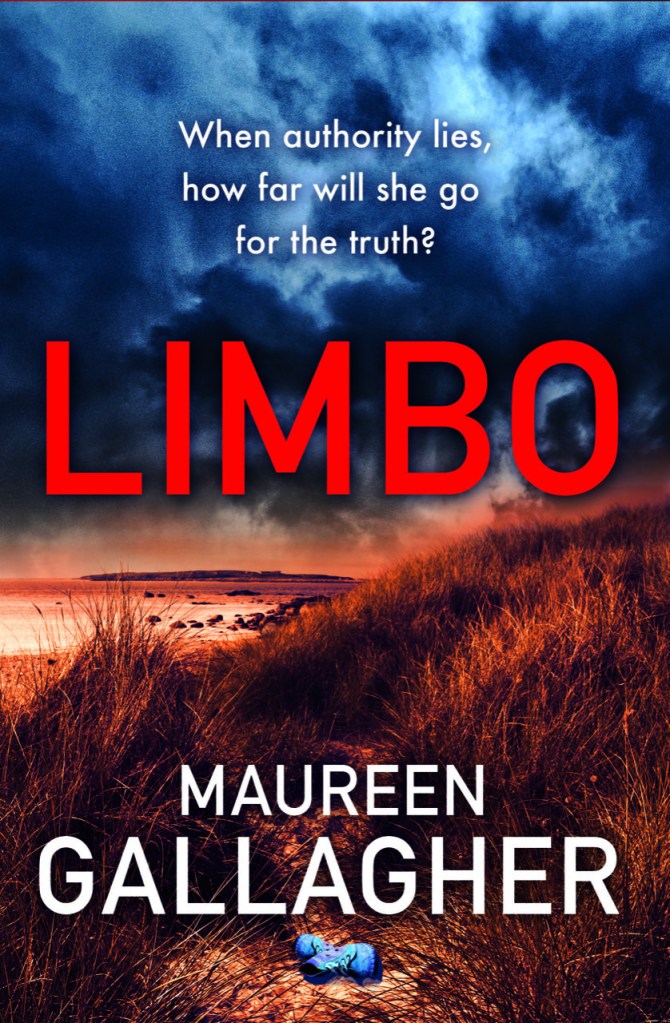

Limbo is the first in a series featuring the brilliantly complicated and humanly flawed Detective Kate Francis whom we get to know as Frankie. Tell me about the cover, the title and the series.

MG: Thank you very much for inviting me to WRITERS CHAT, Shauna. The front cover image of Limbo depicts the dunes at Port Arthur strand in northwest Donegal – marram grass and patches of bright sand in the foreground with a view out to sea and the islands in the distance. The image was taken by my brother-in-law – Peter Trant – an accomplished photographer, who is very familiar with the beaches in Gweedore, and took many photographs of the dunes for me to choose from. The final image is enhanced by David Prendergast, Poolbeg’s designer, who darkened the sky, and skilfully coated the entire landscape with a thrilling orange hue. When it came to choosing a title, Limbo came to me pretty easily, for the layers of meaning that inhabit the word, not least the state of babies souls and the fact that Roche can’t give them a Christian burial. In addition, Frankie’s indecision and paralysis about what she wants out of life career or family is an important aspect in the novel. The title is also in tune with the tone of the book, which is an attempt to imbue the story with a whiff of incense, given the dominance of the Catholic Church at that time. Limbo is a the first of three. My plan is to set the series at ten-year intervals, so that it charts Frankie’s growth and development personally and professionally, and also gives some idea of the way Ireland has changed in the past 35 years.

SG: Very interesting to hear about the ten-year intervals. I love that idea and because I really liked Frankie who is very much of her time but is also an everywoman, can you talk about how Frankie developed both as protagonist and character within the framework of the storyline?

MG: Detective Kate Francis aka Frankie works in a male dominated workplace in nineteen eighties Ireland. Sexism is rife. In the very first paragraph, sergeant Brannigan, ruminates:

‘To think, godammit, the reinforcements they’re sending from the city, includes a woman. A battle-axe, no doubt, built like a barn.’

So from very early on, we see Frankie dealing with the hostility of Brannigan, while at the same time fending off the unwanted attentions of her married boss, and trying to placate her boyfriend, resentful at her long hours at work. As she struggles to advance the investigation, these personal challenges deepen. Her boyfriend asks her: What do you want out of life? To be the best sleuth? To settle down and become a mother? Frankie is conflicted. She doesn’t see why she can’t do both. When she’s left to solve the case on her own, we see Frankie’s professional confidence grow, as she stands up to the corrupt sergeant and follows her own instinct for finding the killer. Alongside this confidence comes an insight into how she will address the apparent contradictions in her life. In the end we see a changed Frankie, one who has grown personally over the course of solving the murder, and who is grounded and at peace with herself.

SG: Limbo is set in 1989 in Donegal, with the stunning landscape key to both the mystery and the reading experience. Your descriptions are beautiful and even more impactful as they are set against the investigation of two murdered babies, from Port Arthur Strand, Gweedore to Errigal Mountain and the River Claddy is “the warm colour of tea”, “On the horizon, Frankie can see the islands floating in the Atlantic, surrounded by thousands of foaming white horses fringing the waves: Gola, Inishmaan, Inisheer.” How important was the setting to the novel and to the series?

MG: I spent most summers as a child in Gweedore in Donegal, where my parents grew up. My father taught in Ranafast, and the family simply decamped to the Gaeltacht for July and August. So many images from childhood mean Gweedore to me: Errigal mountain, salmon fishing, snuff, the bitter winter I spent there with its howling storms; sea and sand and picnics on the strand. Summer seemed to go on forever back then and we spent much of it in one or other of the three glorious beaches, including Port Arthur, which features prominently in the novel. I was fascinated with juxtaposing a horrible crime like the murder of a baby against a backdrop of such exquisite beauty. The idea for the novel came from an assignment at a workshop to write a 300-wordpitch for a crime thriller. The writer, John Fowles, once said that he usually started with a powerful image, and then tried to work out what the story behind it was and how it developed, The French Lieutenant’s Woman being the most obvious example. The image of the mysterious woman at the coast staring out to sea is not so far away from the image of a baby found on the beach. So my novel opens with the most awful crime imaginable. Just as south eastern Sicily is like a character in Andrea Camilleri’s Montelbano thrillers, I wanted Gweedore to feature almost as a character in the story, with the mountain Errigal a touchstone for everything.

SG: Lovely to hear your authorial intention, Maureen, and I do think that comes through to the reader. Over the course of the investigation, Frankie realises how the patriarchal systems of power are skewed towards men, from the hospitals – early on in Limbo a matron exclaims, as if there were no men involved in procreation “these young girls, you’d feel so sorry for them” – to the force which employs her as a detective – she figures out which battles to fight with Brannigan, how to negotiate her desire with Moran (“there’ll be none of that she tells herself”) and her future, whatever that might be, with Rory. Can you talk about your exploration of gender in the Ireland of 1989?

MG: The action takes place in 1989, ten years after the pope’s visit, an era when people’s mindset had not changed much at all from the 50’s and 60’s. I wanted to explore what we were like as an nation back then, and ultimately what that led to: women vilified for no greater crime than becoming pregnant. At one point the protagonist, Frankie, asks: “Do we not value pregnancy and birth in this country?” So you could say my focus was the treatment of women in late 20th century Ireland. When it came to naming my female protagonist, I had to think long and hard. My main reason for giving my female character a name that is somewhat androgynous was because I didn’t want her to be referred to by her first name while all the men in Limbo were referred to by their surnames – Moran, Brannigan, O’Toole etc. I felt that would have rendered her somewhat inferior, in a situation where she is already facing prejudice. But neither did I want to distance her from the reader. So I set about finding a surname that sounded like a first name. Even though there are female Frankie’s, there is the intentional false assumption that Frankie is a male name. At the very least it is gender neutral, androgynous. My intention was to give my protagonist a modicum of gravitas in a male world.

SG: And Frankie as a name for this character works so well. So, part of Frankie’s initial investigations lead her to Umfin Island to meet with members of followers of the Brigid, Goddess of Fertility. She finds

“she’s conflicted. On the one hand, she’s impressed with the back-to-nature self-sufficient element of the lifestyle she’s observed….on the other, at the very least there was a level of violence in the ritual she’s just witnessed that was disturbing.”

In a way, this experience also sums up Frankie’s view of Irish society and politics, and the power of the Catholic Church. It appears to be one thing but actually – including and especially figures in authority – is another. Can you talk about how these themes influenced the story line (or was it vice-versa?).

MG: What was an eye-opener for me when I started to write Limbo, was that the structure of the crime novel – you could say its limitation – allowed me to explore social issues, something dear to my heart. The very nature of the genre frees up the imagination. The two underlying themes I had in mind when starting the novel, was the power of the Catholic Church in Irish society and the subordinate position of women. Someone once coined the phrase ‘the Catholic Taliban’, to describe the hold the Catholic Church had on the lives of women in Ireland all down the century since independence. Throughout the thirties, forties and fifties, and even up to the eighties women’s bodies were a battleground. I wanted to show how the Catholic Church dominated the whole narrative, how it was woven into the very fabric of society, and for this to inform the tone of Limbo. The backdrop to the story is a misogynistic state hand in glove with a powerful church and its impact on women. But I was conscious too that exploring social context should not mean long passages of exposition. The bottom line is that the novel has to be entertaining – people want to know what happens next. Crime writing, like all fictional writing, is best done through scene setting, dialogue, believable characterisation. Or as the late great John McGahern would say, told slant.

SG: Yes indeed – ‘told slant’ – a lesson in writing fiction! Lastly, in Limbo, as in our history, those who don’t confirm to prescribed behaviours and identities are locked up or hide themselves away – claiming their voice as their own by not speaking, for example Hannah. Part of what Frankie has to do is to listen to what is behind the stories that people tell, see what is beyond the land and within the houses. In this way, as Frankie “feels resentful at how the Church has commandeered all the major events in people’s lives”, Limbo is as much about agency and power as it about a thrilling story. Was this your intention?

MG: Limbo is very much about the struggle women have to gain autonomy within the suffocating limitations imposed on them. Hannah’s response to the violent strictures visited on her is to choose not to speak, to metaphorically lock herself away. Her daughter Sarah, in contrast, determinedly manages to rise above her awful experiences and leaves Ireland to embrace a new life. Frankie addresses head-on the challenges she faces and in so doing gains insight into her own personal predicament and how to resolve it. The novel is very much about agency and power. It charts both the tragic predicament of the women who are crushed by their oppression, but also the empowerment and joy of the women who transcend it.

SG: To finish up, Maureen, some fun questions

- Sandy or Stony Beach? Sandy. Definitely not stony – I value my ankles!

- Tea or Coffee? Mostly tea. But when my daughter – who now lives in Spain – visits, I bring her to Tigh Neachtain in Galway, which serves an excellent coffee.

- Music or quiet when writing? I love music but not when I’m writing. I like total silence when I’m writing.

- What’s next on your reading pile? I’m re-reading of Lajos Egri’s superb The Art of Dramatic Writing as research for Book 2, and for leisure reading I’ve started Maggie O’Farrell’s The Marriage Portrait, which I’m enjoying very much.

- What are you working on or thinking about now? Now that the launch of Limbo is behind me, I’m picking up where I left off on Book 2 in early summer. The book’s premise is ‘Misogyny Fuels Femicide’, an idea I’m very engaged with and I can’t wait to get stuck back in.

Thank you, Maureen, for such engaging and thorough answers. I very much look forward to the next two books in the series and to seeing more of Frankie!

Readers can order Limbo here

With thanks also to Poolbeg Crimson for the advance copy of Limbo