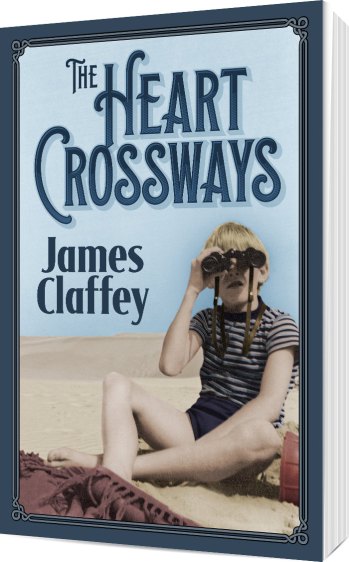

James, You’re very welcome back to my Writers Chat series. The last time we chatted, in 2012, we focused on Blood a Cold Blue a collection of short fiction. This time we’re chatting about your wonderful debut novel The Heart Crossways where you bring us into an Ireland that’s hardly recognisable today.

So, let’s start with language. As a tool it is very much part of the narrative of the The Heart Crossways. Take the wonderful opening section:

“On rainy days the time passes slowly. Trance-like, I tongue my bedroom window and lick the condensation from the glass. My nose smushes against the cold pane. The seagulls glower below, on the roof of the coal shed…”

How much of these wonderful verbs came to you on the first few drafts or was it when you edited the novel that they emerged? I am thinking of what Sheenagh Pugh once said – that great writing is in the editing.

JC: So, interestingly enough, Thrice Fiction Magazine published three short pieces in their March, 2012 issue, and one of those pieces was “Dublin On a Wet Day,” which was remarkably close to the opening beat of the novel. Over multiple drafts the frame of the book shifted considerably, and in several drafts the opening pages were completely different and set at a far different time in Patrick’s life. The image came to me in a memory of my childhood in Rathgar, and how on rainy days my brothers and I would stand at the windows, noses pressed against the glass, cursing the weather that forced us indoors. I went over and over different variations of that opening, changing tense, point of view, at least three to four times, and ended up with a first person narrator that finally seemed to work.

SG: It really is an arresting opening. I love that throughout the novel the power of books comes through. From the old blue ledger the Old Man uses to record transgressions and the books (from Mark Twain to Tennyson) our hero, Patrick, reads to escape. Was this one of those hidden symbols that emerged when you’d finished writing the book?

JC: Yes, I think the books as symbolism emerged through the drafting process, and the ledger idea came to me from an actual ledger from my father’s business, filled with the incoming and outgoing monies for quite a few years, in fact. In several places in the ledger are crude drawings we did of dinosaurs and lions when we were probably bored on rainy days! Further, I wanted to seed Patrick’s world in the literature and drama of the time, the importance that books played in young children’s lives, long before iPhones and Fortnite. I grew up in a house filled with books, drama, literature, and as kids my brothers and I would sprawl in front of the coal fire reading comics, books, and newspaper cartoons, composting that love of books and all things literary.

SG: What beautiful memories, James. The Heart Crossways is set in an era (mid-seventies) when appearances – that you are perceived as good in the eyes of the neighbours and the church – still count for everything. As the Mam says, “All you have in this life is your good name.” Patrick – not unlike Stephen in Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a young man – negotiates appearances and tracks his way through his father’s alcoholism, his mother’s worries and lusting after both Cathy and Mrs Prendergast by using humour. “Seducing Mrs. Prendergast is the mission I have accepted and in silence I try to plan how this will happen. Maybe she will wear a velvet cloak and come running to me like Maria in The Sound of Music?” Patrick is both teenage and reflective in his self-analysis. Can you talk about the development of Patrick’s character?

JC: Patrick began in those early stories as a lonely boy with time on his hands and parents too consumed with keeping hearth and home together to pay him much attention. I suppose there’s a part of him that’s living in his own head, thinking and overthinking life, and there’s a part of him that’s a small boy, desperate for his parents’, particularly his father’s attention. As the book unfolds, he moves from a more simplistic worldview, to one more complex, where he gains some understanding of the complicated nature of life in a Catholic and repressed Ireland. His use of humor as a compass to guide him through the fog of his life is, in my opinion, particularly Irish, in that we use humor to decode, to defuse, and to deflect the missiles life fires at us. And the sex. As a child of the seventies, Patrick is mired in the repression of the time, cosseted by his parents, stifled by the overshadowing Catholic hierarchy that divided the schools into same sex institutions where sex was what Kavanagh called the “wink-and-elbow language of delight.”

SG: A great phrase from Kavanagh! Yes, it is a particularly Irish trait, the use of humour. Continuing with this – there are many laugh-out-loud incidents, for example, when De Valera (the aptly named three-legged greyhound that serves as a pet) chews on the Old Man’s false teeth, or when Patrick gets a bowl cut when the Old Man thinks the barber didn’t take enough off – are any of these taken from real life situations?

JC: Well, we never had a three-legged dog, but some years ago I was in Solvang, near Santa Barbara, for breakfast and there was a American Greyhound Society event taking place in the town. One of the greyhounds was three-legged, and that stuck with me as something that might become part of a story one day. As for haircuts, most of us growing up in Dublin have had our run-ins with the local barber, and mine was with Mr. Roche, whose son was in my class in primary school. We’d tramp up to Terenure Village and enter the barber shop with its red-and-white striped pole, wait for “Skinner” Roche to cut us to shreds, and appear at school the next day to bear the brunt of the insults. Eventually, my mother started taking us to the Peter Mark Salon, a more contemporary place to get one’s “hair did,” than at the “Skinner’s.” My dad always threatened us with the scissors and bowl if we didn’t behave, and my oldest brother grew a ponytail and drew the ire of our Old Man on many occasions.

SG: Oh I remember Peter Mark Salon – still going – it was the height of sophistication! One of the themes I picked up on was that of emigration, and with it, the importance of place – of leaving and returning – creating and re-creating new identities with each new ‘start’. Although the Old Man is a difficult character in every sense of the word, and plays the role of too-little-too-late father (or, as Patrick puts it “a one-man wrecking ball”), I can’t help but think that working on the oil rigs (if that is where he goes to – there is a sense, connected to his drinking, that he frequently disappears) can’t have been easy for him. This must do with economics; the Brogan’s aren’t well-off but they have food on the table and go on holidays. Can you comment on this theme and what it might mean to you, an emigrant yourself?

JC: The Old Man spends three weeks away working the oil rigs in the North Sea at a time, and the work is gruelling and tremendously hard on his body. Patrick’s dad, of course, isn’t used to graft and his body shuts down over time, leading to physical issues that emerge in the latter stages of the novel. Everything the Brogans experience in their lives, scrimping and saving, getting groceries on credit at the local store, are moments from my own childhood. We didn’t have much in terms of financial wherewithal, but we had food, shelter, clothing and warmth, those critical components of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Money for the Brogans is tight, and Patrick’s mother is adept at stretching the pounds, shillings, and pence to make their home as comfortable as possible. For me, as both an immigrant and a child who grew up with not enough money to go around, the theme of economics rings loud, knowing how in my early years in America, I worked a bunch of retail jobs, barely getting by, and only really found my feet financially when I graduated from university and became a high school teacher. Even now, decades later, my greatest fear is running out of money, and I go into a panic mode if our bank account ever gets too close to the bone. I feel my parents’ desperation in those moments and return to those fraught childhood days, until I remind myself I am not my parents and I can make different decisions than they may have.

SG: While religion snakes through the story I found that the sense of loss overtook it. While Patrick imagines “God as a bitter, angry one who takes delight as he metes out punishment to ordinary sinners” he also prays for his own sorrow and torments to end- his relationship with his father. Not wanting to give any of the plot away, the ending of The Heart Crossways was fitting and poignant.

JC: The Church looms large in the story, and the strict Catholic childhood I grew up in shaped me in many ways. I walked away from the whole Mass on Sunday world and found my own way of navigating faith and belief over the years. Today, I identify as a Unitarian Universalist, cleaving to the ideas of Jefferson, Emerson and the Transcendentalists. There’s a freedom, a breath of relief when I’m at a service, with no sense of guilt or shame. As for loss, it defines my life. My father lived his life grieving for the business he lost in the 1960s, never letting it go. He reached his dying day filled with regret, loss and anger towards those he perceived did wrong by him. Being Irish, for me at least, means embracing loss, finding comfort in that feeling, knowing that one cannot be happy every day of one’s life, and that loss is as big a part of life as love, or happiness. Emotions are our weather patterns and there’s a beauty to all seasons, even those that bring devastation to our door. I know this too well, having lived through recent wildfires and debris flows in the area I’ve settled in Southern California.

SG: That’s very poetic – embracing loss. Finally, James, a little on the character of the mother and the Bird. There’s something familiar in both of these and it was lovely to return to them after meeting them briefly in your short stories. Could you talk a little about how characters can re-appear in our writing in different guises, under different circumstances and across genre?

JC: The Bird is a character I brought to life from early flash fictions I wrote about growing up in Ireland. He was a real person, a customer in my father’s pub in Moate, Co. Westmeath. The reappearance of the Bird is timely, after a project I did with Matt Potter of “Pure Slush,”—A Year in Stories. I wrote twelve stories revolving around the Bird, and one of my favorite ones appeared in Causeway/Cabhsair a few years back. In January I returned to the rich vein of material the Bird springs from, and am working on a project where I write a page a day about his life. He never was my mother’s beau, but I remember her commiserating with my father one morning as he read the obituaries in the “Irish Independent,” and announced, “The Bird is dead. The poor auld hoor.” I love how characters ebb and flow in our work, receding for years at a time, only for a re-emergence years later as the tidal patterns of our creativity shift.

SG: I think you’ve just captured the real essence of creativity – the flow and ebb of characters in tandem with our own tidal patterns of creativity. So, to finish up, James, let’s have some fun questions:

- Kindle or paperback? Paperback

- Novel or short story? Novel

- Short story or flash? Flash

- What’s the last sentence you read? “An aliveness that lit up the world,” Michelle Elvy’s The Everrumble.

- Great sentence! What’s the last sentence you wrote? “Oh, poor man. The center of his universe hollowed out and collapsed.”

- Another great sentence! The best jam in the world? Our family’s business is Red Hen Cannery, and we make the most delicious Boysenberry Jam.

Thanks, James for an engaging chat. The Heart Crossways can be purchased direct from the publisher or on amazon. Connect with James on his website.

Below is our chat from January 2012.

*****************

WRITERS CHAT – JANUARY 2012 – ON “BLOOD A COLD BLUE”

Welcome to James Claffey, originally from County Westmeath but now living in Carpinteria, CA, USA with his wife, writer and artist Maureen Foley. James is a prolific writer and his most recent full-length publication is Blood a Cold Blue, a collection of short fiction.

James, tell me about the title and cover of your collection Blood a Cold Blue. Was the title one you had in mind or one that emerged once you had the collection completed and formed? Tell me also about the photograph on the collection, I know you had trouble tracking down the photographer for permissions but was that image of a bird in snow with a crumb an image that you had in mind?

Yes, I submitted the collection to several places and it was always titled Blood a Cold Blue. I chose the title from a line in one of the stories that also bore the same name (I’ve got this habit of titling my stories with fragments from the text). As for the photograph, the publisher, Press 53, sent a couple of early cover suggestions that I didn’t like at all, and then they sent the bird photograph and I loved it straight away. It turned out to have been taken by an Icelandic photographer and he was unresponsive to the publisher’s attempts to contact him. We waited a week or two and there was no word so Kevin at Press 53 said we might want to look at other options including a new title completely, so I went on the hunt for the photographer. All the usual social media avenues were fruitless and on the verge of giving in, I did a last Google search and found an old LiveJournal blog he’d had years ago. It had an Icelandic email address and I sent a message asking him to contact Press 53 about the image and the next day he got in touch with Kevin and agreed to let us use the photograph.

Great to hear it all worked out! You’ve stated that “Skull of a Sheep” is your favourite story in the collection. Can you expand on the idea of having a favourite story?

“Skull of a Sheep” is a fictionalized version of a family vacation in Mayo when I was a kid, and the unpunctuated stream-of-consciousness mirrors the breathlessness of the drive down the country and back again, I found the story stirred my sense of hiraeth, that Welsh word that suggests nostalgia for home, but with some sense of longing for those departed. My father passed away in 2000 and the piece was written right before my mentor and friend, Jeanne Leiby, died in a car crash in Louisiana, so there’s a sense of this story having more weight because of these events. Also, the piece ran in the New Orleans Review, and that is a publication that means a great deal to me, having spent three years in the South, learning the ropes of what being a writer means.

There’s a great sense of compassion, compression and a long breath of emotion in that piece. You capture so much in it – all that lies beneath the landscape and landmarks.

I’d like to hear about how you get into character. Do you have a favourite character in the collection? If not, why not, if so, whom?

I do. The Bird, a character in a couple of stories I’ve written, is close to home for me. My father, if I recall correctly, who used to run a pub/grocery in the Midlands, had a customer who was called by the same name, The Bird, so I found myself putting myself in this man’s head and imagining what it would have been like to wander the streets and fields of my old hometown. I’m currently working on a year of stories for Pure Slush, an Australian publication edited by Matt Potter, with this same character. I find great latitude in taking on the task of creating a life from so few details.

That’s interesting to hear, James, as The Bird is one of the characters that stood out for me. Now tell me about settings. You have some wonderful ones that seep through via the use of names, the turn of phrase (for example “Fragments of the Bird”), from the absurd to the very real and named (for example “Fryday, June 17th, in the year 1681” or “Hurried Departure”). Do the settings come first, or come to you as you write? Or are they sometimes somewhat peripheral?

Thank you. Place is incredibly important to me, and I tend to write with almost reverence about certain locations—New Mexico, Ireland, Louisiana, California. “Fryday, June 17th…” came out of an old print of an Elephant’s skeleton and the story of its death, and I reimagined the actual events of the disaster, which actually took place in Dublin back in the 15th Century. As for “Hurried Departure,” it’s almost a fantastical world slightly based on the area surrounding our house in the avocado trees. Detail, even as liminal as the light over a stand of trees, is terrifically important to give a piece of writing an anchor in the world and as I’ve gotten less naïve as a writer, I find myself noticing the small details of objects and places much more than before.

I think, for me, anyhow, that’s what is so great about this collection. The myriad of different experiences in different settings that you (re)imagine/capture.

On writing, if you’re willing to reveal, what are you working on now?

Well, the year in stories project at Pure Slush, for one. Also, I’m working on an untitled novel with Thrice Publishing, and that’s about a small boy growing up in Dublin with a father who works away on the oil rigs in the North Sea and a mother who struggles at home to raise her son and deal with her own aging mother who lives with them. I’ve also got a novella project I’m collaborating on with another wonderful writer, and I’m very excited about that opportunity. On top of all that I’ve returned to teaching high school English, so I’m having to really be creative in terms of finding time to write, what with my wife and two kids to devote time to, and a dog that needs walking!

That’s a pretty full and creative life! Finally, James, what three books are on your bedside table and what three books are on your ‘to read’ list.

Varieties of Disturbance by Lydia Davis, Bound in Blue, by Meg Tuite, and Gears by Alex Pruteanu, are on my bedside table, and to read are The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt, Transatlantic by Colm Toibin, and A Place to Stand by Jimmy Santiago Baca (a re-read).

Thanks, James, for such insightful and fascinating answers.You can find out more about James and his writing on his website and blog: www.jamesclaffey.com

Andrew! Congratulations. I’ll put you in touch with Nessa. Thanks for reading and commenting.

Andrew! Congratulations. I’ll put you in touch with Nessa. Thanks for reading and commenting.