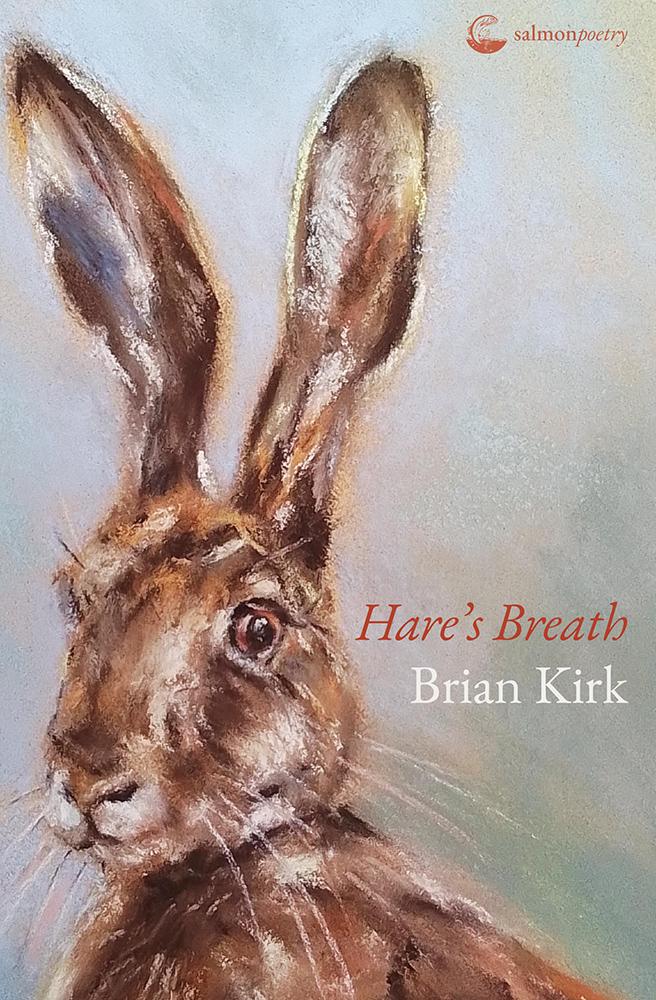

Brian, Welcome back to Writers Chat. This time we’re talking about Hare’s Breath your latest collection published by Salmon (2023). It’s a collection that deserves to be read with care – as much care as you clearly put into the language in the poems and the shape of the collection – and one that rewards the reader with each re-read.

SG: Let’s begin with the title poem, “Hare’s Breath”, which explores the process of living and that of creating. You wrote an early draft when you were resident in Cill Rialaig. It seems without that residency, that poem would not have been written – the landscape, literally, provided you with the theme, the images, and a way (back?) into your creative self. I’m thinking of the opening lines: “I came here to work/but needed to stop.” Could you tell us more about the writing of this poem?

BK: It’s so good to be invited back to Writers Chat, thanks, Shauna. Yes, the poem “Hare’s Breath” came relatively late to the collection and went on to provide the title, so it’s an important poem for me. I was in Cill Rialaig last February ostensibly to work on the first draft of a new novel. I was very much concerned with word count and making progress which is not always a good idea. I did do some work on other poems I was writing at the time while I was there too, but this poem came from my daily solitary walks up Bolus Head. I love walking and the landscape there is so beautiful and isolated. On one of my first walks, I encountered a hare and each day after that I would go looking for it, but only saw it again briefly on one occasion. The poem as you say is about creativity or inspiration – where art or writing comes from and how difficult it can be to grasp it and hold on to it in the world we live in now that is so full of distractions.

SG: As with your previous collection, After The Fall, the main themes in Hare’s Breath are relationships – with family, friends, self, creativity – and time. But here it feels that you’re casting your internal eye back and focusing on the formation of a genetic line in time and place that time changes. I’m thinking of “Kingdom”

….we didn’t lick it off the ground…But we grew up and let him down…dreaming another kind of life outside the fortress that he built from duty, faith and love…His kingdom didn’t last. No kingdom does.

This is also seen in the pairing of “Belturbet Under Frost” and “Googling My Parents” which are beautiful love songs to the past. There’s an emotional weight in these poems which draws the reader back again to re-read. Could you comment on these poems?

BK: I think the past will always be a repository of ideas for me. In After The Fall I had some poems about my parents, but I think I approached them in an oblique way. In “Leave-taking” the picture of a dying father are mediated through the memories of an older brother while I was away living in London. In “The Kitchen in Winter” my mother is conjured from the memory of repeated winter mornings in the place where she held sway. In Hare’s Breath there is more of a sense of celebration of their lives I hope, certainly in the sonnet ‘Belturbet Under Frost’ which re-imagines the beginnings of their love. In poems like “Kingdom” and “Windfall” my father is portrayed as a man of his time, struggling at times in the face of a world that is changing. In some ways he is the child and his children the adults. In “Googling My Parents” I suppose I was trying and failing to reclaim my parents. They both died in the late 1980s within six months of each other while I was living in London, and there’s always a sense of things left unsaid. The closing lines of the poem came to me slowly over time. I was trying to say something, I think, about memory and the human mind, its power and its shortcomings. I was trying to liken the brain/mind to a machine (not a very original simile I know) but that wasn’t enough. I was thinking about that story in the Gospel about the Transfiguration. Peter was bumbling around talking about building tents on the mountain when a cloud appeared and a voice spoke out of it to them. I knew then that that was what I was looking for. My parents speaking to me from the cloud (even if only in dreams). It seemed apt as, after all, everything is stored in the cloud nowadays.

SG: A poignant observation indeed. “My First Infatuation”, “Sour” and “Bully” examine early love and hurt through the eyes of a knowing adult. I’m curious about both the positioning of these poems in the collection and the process of writing them – did they come (almost) fully formed, or did you need to tease them out as part of a reckoning with the past in order to move foreword?

BK: When I’m writing poems I’m not thinking in terms of a collection or where each one might appear in a collection, but when I got to the stage where I sensed I had enough good work to look at putting a book together certain poems grouped themselves. In the case of the poems “My First Infatuation”, “Sour” and “Hydra” I do remember these being written around the same time. They are of a piece in terms of style and subject matter, poems about adolescence, I suppose, being considered from a later vantage point. When I was putting the collection together, I realized that “Bully” sat well in there too and also “Sundays in June” and the most recent poem I wrote for the collection “That Last Summer”. I was concerned I think with re-visiting earlier versions of myself – some of whom I didn’t altogether recognise at first. While writing of these poems, each emerged quite quickly and were then subsequently revised, mainly in terms of the sounds. I think sound is very important in my poems and how they read aloud is key for me when revising.

SG: I can see that, alright. There were a number of your poems that I read aloud to compare the experience of reading them in my mind. I enjoyed the back-and-forth glances between past and possible futures or futures that will now never be – in “Exile”, “Dog Days”, “Multiverse”, and in “Excursion into Philosophy” where you end with that wonderful question “Are beginnings and endings the same?” There is a solid sense of regret but alongside this there is a sharp sense of hope, like you’ve focused a lens in on it. Did you find solace and clarity in writing these poems?

BK: I’m glad you’ve alluded to the future in these poems. I wouldn’t want readers to think that I’m merely obsessed by the past (but yes, I do go back a lot to work things out for myself in the now). The collection is dedicated to my kids and to the future and the book, as it progresses, opens out I hope into a meditation on how the past feeds into the future in a cyclical fashion. I think everyone harbours pain from past experience, but what is really amazing is how, every day, people, even in the most extreme straits, manage to get up again and keep going on. I tend to agree with Joan Didion in that I write to find out what I really think, so there is always a sense of discovery.

SG: Yes, a sense of discovery and a hope that opens up. Hare’s Breath also spans outwards from your life exploring other journeys, the luck of survivors – in, for example, “Hibakusha”, “The Last Days of Pompeii”, “Train Dreams”, “Small Things” – and our impact on nature – in “Houses,” “Seaside Fools” and with that punch of a line in “Gaia”:

We’re dust, and nature doesn’t give a fuck

about our self-importance or regrets:

one day our books will float away in streams

Our own concerns fade into nothing in the bigger picture you paint, and yet, you show us how we – and all that we do, and those that we love – are so fragile and that is what really matters. That acknowledgement of vulnerability and with that a lightness, like in the final poem in the collection, “The Invisible House”, where you end with laughter. Is that the cure for us all?

BK: I think living is a constant coming to terms with things. Community, family, friendships are the things that make it possible for us to continue to live. (I think Covid reminded us of that also. There are some Covid poems in here which seem to fit). In the later stages of the collection the poems begin to look outward more, away from the subjective experience to a broader sphere, taking on social, political and ecological subjects. I’m convinced that being able to laugh at ourselves is one of the most important and one the hardest things to do in life. I hope there are moments of humour in the collection too, in poems like “Seaside Fools”, “The Workshop”, “The Last Days of Pompeii” and “Out of Time.” I’d like to think people will smile from time to time as they read.

SG: We will end with a few light questions:

- Most surprising poem from Hare’s Breath? I think perhaps “The Last Days of Pompeii” because it is the most overtly political poem in the collection. It came in a rush as a kind of ‘state of the world’ poem and on reflection I think I was channelling the late Kevin Higgins who was a great mentor to many poets and had such a wickedly humorous way of making a political point in a poem.

- It has that sense of humour and the punch of politics, like in much of Kevin’s work alright. Coffee or Tea? It has to be tea. I do enjoy an occasional coffee but limit myself to no more than one a day.

- Sea or Mountains? I grew up by the sea in Rush, so it has to be the sea. But I love all things rural even though I’ve spent nearly all my life living in cites or suburbs.

- Do you have a go-to book that you frequently re-read? Yeats’ poetry and lately Derek Mahon’s collected. I do have a look at Ulysses also every few years and I tend to re-read a lot of favourite short stories.

- Quite a wide variety of go-to genres there! Any literary events coming up for you? I’ll be reading at ‘The Listeners’ at The Revels. Main Street, Rathfarnham Village on Tuesday 6th February 2024. After that I’m hoping to get to readings and festivals around the country during the year as much as possible.

Best of luck with the readings and festivals and I wish you much continued success with the collection. Hare’s Breath may be purchased from Salmon Poetry.