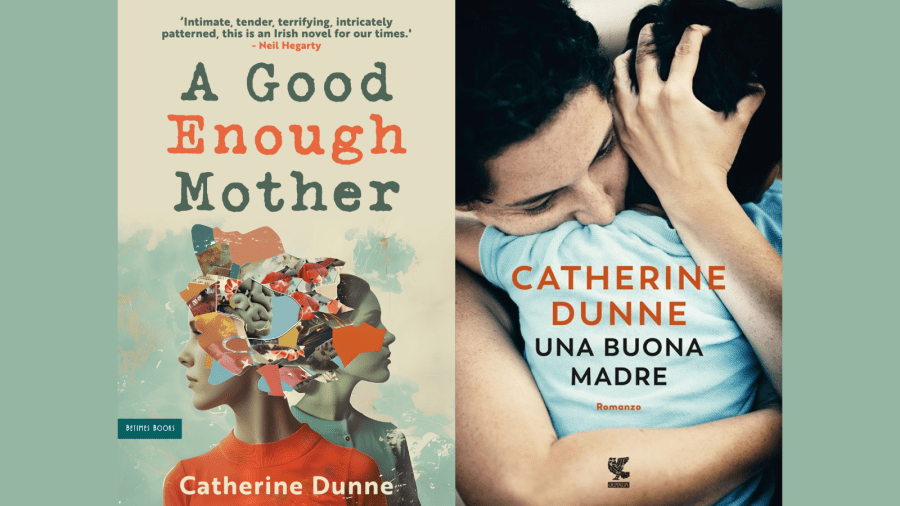

Catherine, You are very welcome back to my Writers Chat series. We’re here to talk about your highly successful A Good Enough Mother, for which you have won the European Rapallo BPER Banca Prize, and the Jury statement about the Italian translation Una Buona Madre (published before this English version) accurately said that in this novel you weave “together the lives of several diverse and ill-starred women” and link “a compelling present to a troubled past”.

SG: So let’s begin with the structure of A Good Enough Mother which is both a history of the treatment of women in Ireland and a beautiful, moving and gripping intergenerational story. Almost every section is dated and named according to whose story we’re immersed in. Can you talk about the mechanics of structuring this complex narrative that spans over several generations?

CD: Thank you for inviting me back, and thank you also for that very kind introduction. Structure is always a tricky issue. But it’s never something I decide on in advance – I tend to let it emerge during the writing. I love being surprised. I love the way the whole process is organic, the way the novel, including its structure, comes to life as I write.

I have always written in scenes. The patchwork quilt is the best metaphor I can come up with for the way I work. The act of sewing becomes a possibility of healing for the women in A Good Enough Mother, and it also serves as a metaphor for the writing process. In AGEM, I chose 66 scenes out of what I had drafted, reworked them endlessly and then sewed them together, like a classic patchwork quilt. I hope the seams don’t show.

The first scene I wrote involved Tess, and it was inspired – if that’s not an insensitive word – by the aftermath of the Belfast rape trial in 2018. That trial, and the not guilty verdict that resulted, convulsed the nation. The appalling public nature of that legal process, the retraumatising of the victim, and the deeply troubling attitude towards women that emerged during those horrifying days fuelled a significant public conversation. It is a toxic attitude that we’ve had to confront again and again in other high-profile cases of sexual assault.

When I began writing the trilogy of novels based on Greek myth – The Years That Followed, A Good Enough Mother, and The Way the Light Falls (to be published in 2025) – my overarching theme was motherhood.

Tess was the first character who appeared to me; and with her arrival, I wondered: what if one of her sons were accused of sexual assault? How would she feel? What would she do? How would she reconcile her unconditional love for her son with her revulsion at his alleged offence? The writer’s eternal ‘What if?’ propelled me into writing her story.

Once Tess’s character began to form, a cast of other women began to clamour to be heard. Catherine Corless’s unearthing of the secrets of Tuam’s Mother and Baby institution – they were not ‘homes’ in any meaningful sense – fuelled my stories of Maeve and Joanie. My research for An Unconsidered People formed the inspiration for Betty and Eileen’s lives in Kilburn, and so on…Each character led me to the next – the kind of organic growth of narrative that I referred to earlier.

SG: That’s really interesting about letting the writing lead organically, and the practice of writing in scenes (and no, the seams don’t show!). This novel gives voice to that which can’t always be voiced – the violence of assault and rape – and in such a way that this narrative threads through and above each of the individual narratives. And yet each of the narrators have a very distinct narrative voice which is not an easy write. Did the movement from silence to voice come as you were stitching the novel together?

CD: Time and place were my friends in this regard. The sections of the novel move between the 1960s and the present, back and forth from Dublin to London, and to an unidentified location somewhere in rural Ireland. ‘Seeing’ each character in their distinct location, and at different times, made their individual voices begin to come alive inside my head.

I always find it interesting that the character closest to me in age/location/circumstance is always the most difficult to write. Familiarity is my enemy. I struggled in the early drafts with some of Tess’s scenes. I had to take the decision to place her on constant high alert, to make her anxious and fearful for her family. That anxiety became one of the defining features of her voice.

With Eileen, I drew on my extensive research for An Unconsidered People. Years of going back and forth to Kilburn, interviewing elderly Irish immigrants, meant that my sense of London in the fifties and sixties was already part of my imaginative landscape. And I was able to give her a passion for fabrics and sewing, all of which helped me develop the individual nuances of her voice.

This novel took me about four years to complete. During that time, the characters became my friends and I saw them as individuals. The more time I spent in their company, the more I grew to love them and the more real they became.

Writing is an act of imaginative empathy. The predicaments I created for each character were different, the challenges I gave them were demanding in different ways. Each draft of the novel meant I could stitch in more and more detail about their lives and their attitudes that made these fictional characters differ from each other.

SG: I’m glad you refer to drafts (multiple) and the process of stitching in more detail. You’ve spoken above and in The Irish Examiner about how Tess’s narrative came to you fully formed and was then followed by Betty’s story. Tess recalls that:

Family is family, Betty used to say. You fight with them, you fight about them, but above all you fight for them. Tess stands up. She needs to find her fight again. Needs to access that spirit that will help her to reach Luke. No matter what he’s done. Then she switches off all the downstairs lights…

I loved how you anchored Tess’s story in the continuing running of a household, the shopping, the cooking, the simple turning off of lights. There was something so moving about the simple, every day actions that carried the weight of terrible violence. Can you talk about Tess and her movement through the novel?

CD: Tess has to deal with one of every parent’s worst nightmares. Luke’s challenging and dangerous behaviour, the accusation he faces, the threats to her family’s wellbeing are all emotionally draining. But despite being consumed with worry, Tess is anchored in the real world. She has a job, an absent husband whom she loves dearly, but financial realities mean that he is frequently away from home – a source of significant tension between them. Tess must manage home and family – Luke and Aengus, her two sons – on her own.

Despite the crisis facing her, Tess still has to deal with all the tasks that I believe sociologists call ‘love labour’. She needs to cook, to clean, to shop, to keep the household running so that everyone gets fed, everyone has clean clothes, that the home environment doesn’t descend into chaos…

Research tells us that most of this kind of work is still carried out by women. Whether women willingly assume responsibility for these tasks, or whether that responsibility is thrust upon them is another day’s discussion. The daily reality that I create for Tess is familiar enough, I believe, to be recognisable to most readers.

I also tend to bristle that domestic detail such as making a list for the supermarket, or picking clothes up off the floor, or trying to put a meal together under pressure, has frequently been dismissed as ‘small canvas’ stuff in women’s writing – as though the domestic is not a fit subject for fiction.

In an essay entitled Writing for My Life, I observe:

I’ve experienced the accusation many times that women work on too narrow a canvas: that of the ‘domestic’. The wider world, that of big issues and important causes, belongs to men. It’s an argument that might also be familiar to Jane Austen.

In the Odyssey, Telemachus tells his mother, Penelope, to be quiet. He tells her: ‘talking must be the concern of men’.

In this version of the tale, she obeys; we don’t know how she feels, but she obeys.

He means, of course that talking – all the public, the weighty, significant discourse – must be carried out by men. The chatter can belong to women, tidied away into their domestic spheres among the dishes and the brushes.

And so, I like to give the dishes and the brushes their own special place in my fiction.

SG: Thank you, Catherine for such a full and brilliant response which puts me in mind of the importance and power of the domestic in the fiction of Elena Ferrante. Those dishes and brushes are witnesses.

I found Joanie’s narrative particularly heartbreaking and you voice her confusion and naivety in St Brigid’s, the Mother and Baby Home so authentically.

“Joanie imagined that the girls, the penitents, must use up every single punishment in the whole world, so that nothing was left over for the nuns.”

And then after her baby is taken away,

“Joanie’s howls filled the long corridor and ever since, she’d wandered about like a lost ghost, trapped somewhere between two worlds.”

It felt like she stayed trapped between two worlds for most of the novel. Was some of her story based on your extensive research for your non-fiction book An Unconsidered People: The Irish In London?

CD: Nottingham was one of the cities I visited briefly during the time I was researching An Unconsidered People, but my main focus was Kilburn and Cricklewood. However, in one of the many mysterious ways that ideas and memories float to the surface during the writing process, Nottingham came to me as somehow fitting for Joanie and Eddie.

As before, familiarity has its dangers for the writer, and I wanted somewhere to place Joanie that I didn’t know as well as I knew London. I wanted a place that, within the world of the novel, was special to Joanie. And Nottingham just…elbowed its way to the front of my mind. I had to research its parks; its houses close to the railway station; its hotels. None of those places was familiar to me, and that was a gift. All of it became food for the imagination.

Maybe, like parents, novelists shouldn’t have favourite characters. But Joanie is mine. I have to confess that. Perhaps because her life experience is light years away from mine – she’s from a poor rural background; she’s treated harshly by her parents; she’s dyslexic. Her predicament elicited the most empathy from me.

Her story has so many echoes of the stories I read of some of the 56,000 women incarcerated in Ireland’s Mother and Baby institutions. I wanted to give those stories space and dignity – and so Joanie arrived in my imagination.

SG: Maeve’s father drives her to St Brigid’s. Maeve tells us

“I don’t know which was worse: being betrayed by the boy I loved; feeling frightened about what lay ahead; or knowing that my father was lost to me for good.”

Later, she tells us (in stunning prose!):

My days began to fill up with possibility. Hope became a bright blur, the colour of sunflowers. At the same time, I kept thinking about this secret army of women. All of them – all of us – all over Ireland. Mothers of lost children.

These are themes you deftly thread through the novel – boys and men betraying and casting women into hidden spaces and places, and women together creating bonds of safety and possibility.

CD: I remember, even as a young teenager when I became aware of the power of words, that I wondered about the phrase ‘unmarried mother’. In the 1970s it was still a loaded term, redolent of shame and immorality. It was one of those phrases that filled my generation of young women with a terror of getting pregnant.

But even then, another question became insistent: what about unmarried fathers? We never heard a word about them. Did they not exist? Were these so-called ‘illegitimate’ babies the result of mass miraculous conceptions all over Ireland?

It would be years before I even began to understand the potent nature of shame as a method of social control. Years before I learned that around the time the Irish state was founded, there was the belief that the value of such new states resided in the virtue of its women. It therefore followed that if the women that populated these newly formed states were not ‘virtuous’, then they needed to be hidden away.

Hence the development of Ireland’s ‘shame-industrial complex’, as Caelainn Hogan calls it. Magdalene Laundries, Mother and Baby institutions: all of them methods of the social control of women, a system devised, developed and maintained by Church-State collusion. Photographs of the time show that the power of both the Catholic Church and the Irish State was entirely in the hands of men – a symbiotic relationship that was at the root of this country’s problematic relationship with women and women’s bodies.

In the world of the novel, I wanted to give life to what I have so often observed: the ways in which women work to strengthen social and familial ties; the way they support and nurture each other as a way of challenging the misogyny that is still such a part of modern society.

SG: And we don’t always see these ways in which women support and nurture each other. Furthermore, you tackle difference with acceptance and tenderness through the wonderful Eileen and all that she does for women. She was my heroine of A Good Enough Mother.

Sometimes, when I look around at the three of us in the evenings, I have a powerful sense of being bound to a great circle of other women, other times. Our tasks feel ancient, full of history, the threads of connection pulling us tightly together as we work.

Can you talk about her formation and the role of material, thread, sewing and mending?

CD: I loved Eileen’s steely defiance. That’s where she came from: her refusal to bend to what was expected of her. Her character, and her life experience, came from some of the many stories I listened to in Kilburn and Cricklewood over the years.

A nurse I interviewed – who chose to remain anonymous in An Unconsidered People – told me about her uncanny ability to detect even the earliest signs of of pregnancy in the young women arriving at Euston Station, alone and terrified.

She used to meet the mailboat each morning and said that her ‘mission in life’ became helping those pregnant young Irish girls, who had been sent away lest their condition bring shame on their respectable families.

She had the insight, however, decades later, to wonder whether she would have to account for her actions on the Day of Judgement.

What actions? I asked.

In the belief that she was doing what was best, she handed over dozens of newborn babies to good, Catholic families in London – babies born to those terrified Irish girls – without any paperwork whatsoever. She did not profit from this in any way, but understood, years afterwards, that these transactions may not have been ethical.

Her ‘mission in life’ made me ask the eternal writer’s question: What if? What if Eileen had been one of those girls? What would it have been like to search for your lost child for the rest of your life?

Her name, Eileen, is in memory of my own godmother. A most beautiful human being, who had no children of her own, a grief that stayed with her all her life. My character, Eileen, is named in a loving tribute to her.

SG: That’s beautiful and what a loving – and lasting – tribute to your godmother. We will end with some short questions, Catherine:

- Cats or dogs? Oh, dogs, every time!

- Mountains or Sea? Sea, with mountains a close second.

- What do you do after you’ve published a novel or a long manuscript and had a launch? Usually, mourn its absence for a bit, before diving into something new.

- One stand-out fiction and non-fiction book of the year for you? Not sure what year it was published, but I loved Wifedom, by Anna Funder – non-fiction. A blend of so many forms of writing. And far too many novels to choose from, but if you insist, Soldier Sailor by Clare Kilroy and Our London Lives by Christine Dwyer-Hickey.

- What are you working on now – if you can talk about it in a general sense, I know it’s not always possible to articulate what’s not yet formed. I’m currently working on The Way the Light Falls – part of the trilogy of novels inspired by Greek myth. It has already been published in Italian and was shortlisted for the Strega Prize for Fiction. But I’m glad to have the opportunity to revise it before it’s published in English by Betimes Books sometime in 2025. But, as a little bit of superstition, after 30 years as a professional writer, I have the opening paragraph of a new novel already written…There is always the lurking fear that the writing well might run dry!

Thank you, Catherine for such enlightening answers and insights into your process. I wish you continued success and look forward to The Way the Light Falls.

Purchase A Good Enough Mother

Listen to Miriam O’Callaghan’s interview with Catherine Dunne on RTE