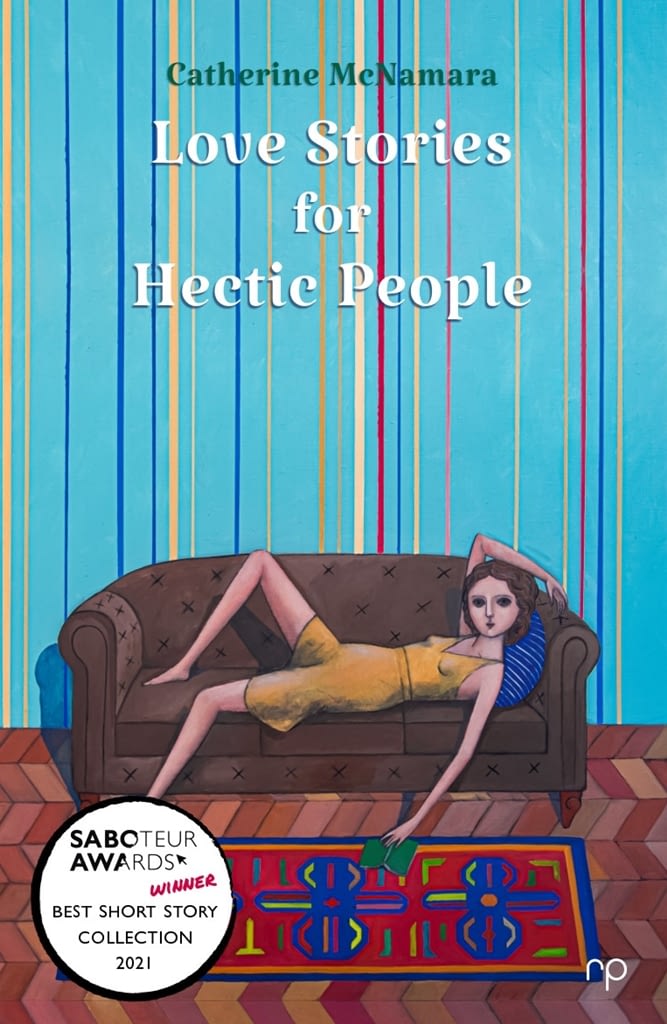

Catherine, Welcome back to my WRITERS CHAT series. Today we’re discussing Love Stories for Hectic People, a slim volume of thirty-three charged flash fictions which recently won the Saboteur Award for Best Short Story Collection (congratulations!)

SG: Firstly, let’s discuss the title and cover. It seems that these stories are not just for hectic people, they are about hectic people though much of what is explored in this collection is reflected by the cover image of a woman in a yellow dress pausing in her reading with the sense that she is full of feeling.

CMN: To be honest this title came about for another collection that outgrew its intention and vibe. I knew with the very first story – ‘As Simple as Water’ written first and barely edited – that I would be addressing the many shapes of love, so that would involve an array of people immersed in different lives. So Love Stories for Hectic People very quickly glued itself to the story series, which was written over the course of six months, until I reached the final piece – ‘Love Is an Infinite Victory’ – when I knew it was complete.

The cover image came afterwards, once the book had been accepted by Reflex Press. Before the pandemic I was in Venice for an opening, where I met an old friend who is a painter in Florence. I told him about the book of short fiction I’d had accepted, and he said why don’t you have a look at some of my works? This image spoke to me from the start and I can’t say how happy I am with it.

SG: What a lovely story about obtaining the image – so full of artistic synchronicity!

I love your use of brackets to bring the reader into the other side of the narrative. In “As Simple As Water” we meet Vasilis K and Marj B in Athens train station after the moment when Marj has fainted. As a woman – a stranger – helps Marj, Vasilis stands apart, watching:

Vasilis who has been making love to Marj most of the night (except when she wept in a corner of the bed and he waited) wonders about the pelvic cavern of all women which is filled with jostling organs and squelching tubes and lengthy orifices like vivid botanical sections drawn into slithering life.

So much is captured here – the stretch of time, of physicality, of distance and the point in which Vasilis removes himself from Marj. Can you talk about how you capture the depths of character and narrative in these short tales?

CMN: It’s going to sound very crazy but when I am in the zone and writing cleanly, it’s almost as though I am hearing a voice dictating the scene in my head, and I have to get it down quickly, and then halt before it turns to jibberish. Half of the time I am trying to slow and clarify what comes to mind, and make sure I am being faithful to the tract of the story, with some sort of carrot dangling ahead. Maybe it is madness. But I prefer to think of it as magical composition. Almost musical. Of course the downside is that sometimes it is irrelevant and nonsensical, or doesn’t piece together, but for me, this sort of freestyle writing sometimes brings me to the brink of lucid swimming ideas directly from the subconscious, which can be surprising and powerful. I do think writing is very much a practice, so one needs to find out what works best to produce some sort of truth or an honest portrait of some aspect of humanity. The brilliance of flash fiction is that you have zero time to get to the point, so you have to know the core of your story from the outset – and deliver! It’s a great, risky form.

All of the above said, I know that with this story I wanted to include the reader in the events leading up to Marj’s dramatic fainting at the train station, through the lens of Vasilis’s recollection. I don’t think the use of bracketed, almost-overview inserts works for every piece of work but in this case it seemed to fit with the raconteur style of voice. I think it helps us feel Vasilis’s discomfort and detachment within the fluid rush of action as it occurs, showing how the lover with whom he had been intimate is now a collapsed woman on a metro station floor and, later, a patient in a hospital, away from whom he walks back into his own life.

I think that to capture any sort of depth or truth you have be the character and be wholly faithful to how this person might act and react – even if this means changing the course of the story or using a certain voice or language style. Flash is brilliant for the shifting and intensity that it both allows and demands.

SG: You mention risky and flash together and I think with this collection you do take risks and even as you say, in the way you experience the dictation of the story and you get it down without letting the rational critic emerge.

As with much of your writing, it is through the senses that we get to know the characters. “Genitalia” captures the lived experience of periods, the messiness of our organs and the desire – by some – to tidy it all up, and in doing so, make women neater.

I loved the recollection of the unnamed woman painting “a line of hieroglyphics …on the yellow wall” of a hotel and that by now “the piece of mortar she painted would be lying in a pile of rubble along the river. Where it gleams at night” and how, at the end of this story, by becoming pregnant, all is calm again.

Can you talk a about how many of the stories here explore the power of the female body?

CMN: I really wanted to celebrate female blood in this story – a celebration of our moon-guided, timeless cycles and our power to reproduce. For me, the guy is almost irrelevant, in that he is so poorly informed about the wonders of the female body, and he has been grafted onto this young woman’s wondrous existence. I wanted to show that he would learn from and be enriched by her. Men are sometimes a little repulsed by the force and power of our bodies, and how we have this intrinsic connection to the tides, and even the gods if you like. I wanted to take up that thread and show this woman as a wild modern goddess.

SG: Yes! Many of the stories use sensory memories – or the creation of these memories, in “Citrus”, for example – to connect the child-self with the adult-self in the way that power permeates experience. Here the narrator – suffering abuse – notes that “Everything is fury, everything is rivalry.”

In “Slaughter of the Innocents”, power and police abuse of it simmers dangerously, represented by the “insignias on their shirts”, “a stitched leather holster nursing a gun” which make the narrator realise that she hates her father more than she loves her own life.

Can you talk about this theme of power and control?

CMN: I have experienced something of the violence of men and how this can filter down as a refracted code through a family. It’s something I know I will write about more. Probably anyone who has ever lived through violence is always one step away from this terror. So I think it is something I listen for when I am fishing for ideas, or when people tell stories.

The other thing I find is that we see so much violence on-screen that we are anaesthetised, so I think that my job as a writer is to strip back domestic violence to its daily tension and core dynamic, more than an orchestrated, visual drama. I wanted to get inside of violence with words and make the reader respond in a visceral way, perhaps striking familiar cords, but certainly in a more subtle way than televised or cinematic violence.

SG: That story deftly captures the refracted code of familial violence.

Languages and travel – and the liminal spaces between understanding and comprehension – add to the sense of surreal (and humour) in these stories. Often bodies and minds experience love separately.

In “Tokyo Frieze” Tanja and Kurt “always spoke freely; he with his accent and she with hers. Perhaps because of the zigzag through languages they were emboldened when addressing each other’s eyes.” Later Tanja recalls when she was younger and “had felt porous, hyper-human, tied to a common energy or saturation. But now she knew she was confined within the body around her and went no further. Her history was a stream of dioramas like this.”

I thought your use of language and travel as a way to delve into aging and the body was interesting. What are your thoughts on this?

CMN: It’s so true and curious the way that bodies and minds experience love separately. I love this zone!

‘Tokyo Frieze’ is one of my favourite stories in the collection and was originally published in Rowan Pelling’s The Amorist magazine. My interest in language and the languages of love stems from the fact that I left Sydney at 21 and though I speak English a lot of the time, I have lived in countries where other languages are spoken, and have learnt French and Italian, and am now studying Greek. So the characters in my life have mostly been European or West African, and I am fascinated by accents and attitudes and words. Travel too, as well as living in a foreign context and feeling at home within it, also figure in my experience so these aspects have become reference points for my stories.

In this way, utilising language and travel to address aging and the body, has been a natural modus operandi, in that my reservoir of story material comes directly from these areas. As I grow older as a female, a mother, a lover, a writer, a traveller, it’s not so much about recounting experience, as using the emotions generated by certain experiences in order to give authenticity to the stories that come about.

SG: I love how you express that, Catherine.

Using emotions generated by certain experiences in order to give authenticity to the stories that come about.

In essence, writing from what you know into what you don’t know.

Let’s end with five fun questions.

- Coffee or Tea? Coffee – espresso!

- Sandals or runners? Sandals

- Sparkling water or non-carbonated? Non-carbonated

- What are you reading now? Gina Frangella – Burn Down the House

- What are you writing now? Novel rewrite and some budding flash stories

CMN: Thank you for having me again Shauna!

SG: Thank you, Catherine, for the joy reading your collection brought me and for your generous answers in our Writers Chat. I wish you much continued success with the collection.

Thanks to Catherine McNamara and Reflex Press for providing me with a copy of Love Stories for Hectic People.