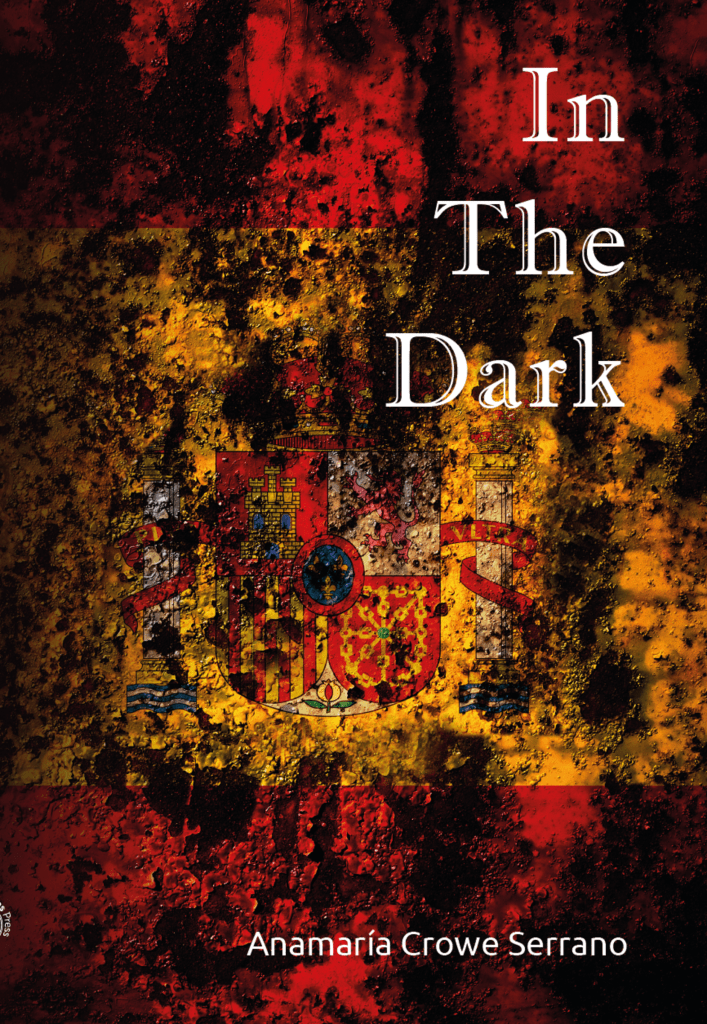

You’re very welcome to my Writers Chat series. We’re going to chat about your debut novel In The Dark (Turas Press: Dublin, 2021), which, from its captivating opening brings you right into the world – the house – of sisters María and Julita in north-east Spain, 1937.

Buy In The Dark from Turas Press

Disclosure here: I’m working on a trilogy set in the Spanish Civil War in the north west region of Asturias (prompted by my father-in-law, an extract of which was published in Reading The Future (Arlen House: Dublin, 2017)) so I was particularly interested to read about your personal connection to this period in Spanish history. I’d love to talk about personal connections, the difficulties in writing from personal history and on the ground research but that would take us too far away from your wonderful novel that we’re here to discuss!

SG: I read In the Dark in two sittings – I couldn’t put it down! So let’s start with the writing. From the brilliant opening and daring style, you exhibit real control over the language, moving the narrative along and introducing us to the characters in ways that keep us engaged and make us care.

Bar Joselito. The bustle and Joselito’s widow, Encarna, are one and the same thing. Encarna is tables and chairs. She is indoors, outdoors, shutters open, sawdust, chalkboard. She is tinkling glasses, barrels and rolling laughter…..

I don’t think I’ve ever read an opening in this style that brings character, setting and movement into such sharp and wonderful focus! Can you talk to us about the style of this novel and how it was for you to write in this form? Did your vast experience of poetry and translation influence this style?

ACS: Thank you, Shauna, for taking the time to read my novel so carefully and do this interview. Your own trilogy sounds fascinating. I really look forward to reading it. It seems that there’s a lot of interest in the Spanish Civil War at the moment, especially in Spain, of course, now that this generation have the benefit of hindsight from a remove of several decades.

Coming back to your question, I’m delighted the style grabbed your attention because style is the most important thing for me. I’ll put up with a less than satisfactory plot in a book I’m reading if the style is beautiful. Finding the right mode of expression took a while, but rather than force anything, I put the writing to one side for a year or two and did a lot of reading instead. It was a bit scary not having a clue how to go about writing, but I had to trust that the ideas and inspiration would eventually come. And they did, thanks to three books in particular whose styles jumped out at me and made me realise that what I was after was something very spare and evocative with a strong visual dimension. It’s no coincidence, I suppose, that the three writers of those novels are also poets. They were Han Kang’s The White Book, translated by Deborah Smith, Maryse Meijer’s Northwood, and Robin Robertson’s The Long Take. I loved the fragmented structure of their work, the silence of their blank spaces.

As you point out, my own background in poetry definitely influenced what I liked and how I wrote. I’m used to brevity and enjoy playing around with mood, distilling it to create more impact. When it came to writing from the point of view of the man hiding under the stairs, his thoughts fell naturally into an even briefer style that reflects the cramped dimensions of the space he is in, the lack of air, the disintegration of his state of mind.

SG: Thank you for such an expansive answer. I’m not familiar the writers or the three books you mention but I really must seek them out – the idea of the silence of blank spaces is fascinating.

The main story of In the Dark – and there are many stories within this novel – is narrated by the sisters, María and Julita, and through the secret the house holds – the man locked in the dark room under the stairs. I enjoyed the alternating viewpoints and how, as the plot was revealed to us, you brought in more narrators, including, the interesting (and brief) one of Julita’s son Fernando. Can you talk a little about how this device of multiple narrators served to unfurl the plot while keeping a steady pace?

ACS: The characters that take refuge in the house were good fun to write, I must say. In the beginning, I brought them in partly because I wanted to build tension – with all these people around it becomes more difficult to take care of the deserter under the stairs. But somehow their lighter side emerged and it was interesting to examine the way they could change the dynamic between the sisters. You are right that they also serve to provide their own stories. In some ways they highlight the horror of being stuck in the middle of the war with no homes of their own, unsure of what will happen to them even when the war ends. Through their political comments I also wanted to convey the complexity of the political situation, how ordinary people could only have a partial understanding of what was happening in Spain because the information they got in the media was censored or very biased. In that regard, Fernando, who is home on leave after almost a year, brings hope to the house, but knows he can’t really tell the family the truth about the disorder at the front because the family wouldn’t believe it. He, too, unwittingly becomes part of the censorship machine.

Something else that I was keen to get across was the power that creativity and the imagination have in helping us endure difficult circumstances. That’s where Fina’s character came in. She’s the dancer, the antidote to war, completely misunderstood and even ridiculed by characters who hold extreme views that lack flexibility or imagination. But her presence in the house is transformative for more open-minded characters.

To keep the plot moving forward with all these different voices vying for attention, I had to pace it carefully, making sure I interspersed the voices sufficiently, giving them turns to speak. At the editing stage, I had to juggle them a bit to make sure it worked and that no particular voice dominated.

SG: What a wonderful insight into your writing and editing process, Anamaría! In the Dark is set in Teruel, north-east Spain in the winter of 1937. We get a very convincing picture of the city yet it felt like a character, even an everycity – almost universal. Part of this is because of the descriptive and sensory language you use throughout the book to place us with and in character and show us the narrative drive.

“It’s easier for a village to swallow the darkness when there’s a rumour of light”

“Every cell in María’s body is bursting for fruit. A town is a living thing, she thinks, her progress almost static through the rubble. But shops and houses here are no more than skeletons of buildings. A town is its people. Dies with its people. Wheezing, spluttering, crumbling to demise.”

“Time expands and the world shrinks to the size of the house.”

Can you talk a little about the importance of place in In the Dark?

ACS: That’s a great question. For me, there are always two aspects to a place: the physical aspect – which has to do with its architecture, layout, geographical location – and the emotional aspect – which is its people and everything that goes with that. The two are usually interlinked, but people are ultimately more important than buildings, so in some way, there is this very human element to places that makes them what they are. I’m always struck by devastated cities in war zones. They hardly can be called cities anymore because so much of them is demolished, but as long as there are still people living there, trying to survive, we refer to cities as though they still exist – “this is such-and-such a place”. Once the people are gone, though, the place ceases to exist and is written into history: we say “that was such-and-such a place”.

The relationship between people and place gives the city its personality. There are places like public parks, libraries, that to me are a bit like friends. You go there to connect with the place because you want the feelings that it produces in you, you feel comfortable there in a similar way to when you pick up the phone to a friend because you want that particular connection. I think it’s why it seemed quite natural in the novel to personify the city sometimes. Like a character, as you say.

When the city changes dramatically because of a war – or a devastating flood like the one I witnessed in my teenage years in Bilbao – it’s as if some part of you dies with it. There’s a huge sense of loss. It takes years to rebuild a city and, even then, it’s never the same again. This, too, was something I wanted to capture.

SG: I love the idea of the public places/amenities being friends. You paint a convincing picture of sibling relationship – and all its nuances – in the characters of María and Julita and is, at times, most interesting seen through the eyes of the man in hiding who says they are “so unalike as sisters”. They represent different factions in the war – Nationalist/Fascist and Republican/Democracy – as well as different types of femininity and in their relationship to motherhood. Can you talk about the characterisation of the sisters?

ACS: With María and Julita I wanted to create characters that were complex and that, in Walt Whitman’s phrase, contain multitudes. I wanted characters that revealed one face to the world but who had another side to them that was less obvious, less understood. Julita, who supports the Communist party on the Republican side, comes across as bossy and insensitive, belittling others as a way to purge her inner pain – her husband was drowned in the war, after all, and her two older sons are fighting at the front – but in her own way she is selfless, staying in the besieged town to help María, and always doing whatever she can to help the war effort. María, on the other hand, appears to be generous in offering her home – albeit reluctantly – to the refugees, but she is grieving for her infant daughter, and finding it hard to cope with the tension that is building with the arrival of the refugees. She also dithers in her political position. She’s not fascist, but she questions what is happening in the Republic, the methods that are being used to bring about social reform.

I wanted their relationships with the important men in their lives to be less than straightforward too, in some ways because that’s often how life is, but also to hold another mirror up to the many ways that life and human relations disintegrate during war.

One key thing about the sisters that I wanted to convey was their resilience and their ability to adapt to the horrors of war. Women everywhere form the fabric of society, which is especially important when times are tough. It is a role that has long been undervalued across the world, but the quiet domestic role women play is like the soul of society – the unseen pulse that is vital for everyone’s wellbeing. Both María and Julita fulfil this role in their very different ways.

SG: For me, one of the strongest voices was that of the man in hiding. You capture the physicality of his space – both physical and head – through your use of space and the page. One particular scene that struck me was one in which he experiences PTSD when he is trying to think of María:

…still pain persists–if only I had a cigarette [….] my whole body flinches–if only I could deny this body–disown it–be someone else…think–think her dark–her fingers slim around me–think the soft–her mouth–her tongue–the bullet–no–think–think […] think her soft–his guts–his–fuck–NO–María think–please–María please–his hole–his head….

Can you talk about the role of this narrator and how he holds the book together – being the voice of the war and of the house?

AMC: During the Spanish Civil War, like in many other wars, there were men who spent long periods of time, sometimes decades, in hiding so as not to have to fight. They lived in tiny spaces, the size of a coffin in some cases, or in attics, or under a stairs, with just one person, usually their wife, helping them. It was a horrific existence. In Spain they’re called “topos” (moles) because they often went blind from living in the dark. That’s what gave me the idea for this character.

He deserted from the war because of the atrocities he saw at the front and because his political allegiance shifted as the war progressed; he doesn’t want to fight for a cause he no longer believes in. I think many people in Spain at the time didn’t quite understand the full implications of the political situation and were misled by their leaders. George Orwell, famously, understood it but even though he wrote Animal Farm from his experience of the Spanish Civil War, that aspect of the Republican government’s vision for Spain doesn’t seem to have filtered much into the public consciousness. I wanted the man under the stairs to have the kind of clarity that other characters lack. It is ironic that his voice, the only one that seems to understand what’s happening politically, is silenced. He is physically in darkness but he has insight into the government’s mismanagement of the country, whereas the other characters are getting plenty of information from the media but, because of the censorship and propaganda, they are the ones in the dark as to what is really happening.

His desertion also represents a moral dilemma that runs throughout the novel. He is doomed to think about his position, which in many ways is an act of cowardice, while he watches everyone in the house through a crack in the wall. Even though he has no contact with anyone except María, he has his own kind of relationship with everyone in the house from his observations of what’s happening. He’s like a common denominator no one knows about. I hope readers might be conflicted about him – and other characters – even though there’s good reason to be sympathetic towards him. The more I researched this novel, in fact, the more I realised that people fell victim to circumstance in the lead-up to the war. It would seem wrong to judge from our privileged remove. Yet the moral questions remain for us to mull over.

SG: Although In the Dark is about war and how it destroys countries, villages, communities and families, it is also very much about the domestic and how women (María, Julita, Encarna, Fina, Senora Rojas) and children try to uphold a sense of normality and keep both families and communities surviving. I particularly enjoyed the struggles and triumphs of birthdays and Christmas and the joy – the times when “for a whole evening no one has thought of the war” – when in reality, “Moral is a fragile thing. Like happiness.”

How important was it for you to convey the domestic alongside the war?

ACS: This was one of the most important things I wanted to convey, apart from the political conundrums. Books about war, whether fictional or factual, seems to focus mostly on the fighting, on strategies, supplies for troops, but there is less mention of the women and children and older or infirm people who are living in the middle of a war zone, struggling desperately to stay alive in their own homes. I was very curious about this and wanted the novel to portray the resourcefulness of women. They had to adapt constantly to all kinds of deprivations – freezing temperatures, electrical outages, no running water, little fuel or food, poor access to medical services, blocked and/or dangerous streets, children at home because schools are closed, homes damaged by shelling… The list is endless.

The amazing thing is that humans somehow manage to rise above extreme hardship and find ways of bringing moments of joy, like the festivities you mention, into the day. It’s important to do that in order to counterbalance the grief and uncertainty. In the novel those celebrations tend to revolve around the children, but it’s clear that they are as important for the adults. So is the semblance of normality that you mention. The family play cards in the evening as they always have done. When the women go out, they make some effort to look well even though they have very little. They wear lipstick or use a good hat pin. It’s important to cling to some element of dignity, of one’s former self. It’s what keeps people sane.

SG: It’s so true what you say about how we “manage to rise above extreme hardship and find ways of bringing moments of joy into the day” – and that’s something that you capture so well in this novel, In The Dark.

So we’ll end this Writers Chat, Anamaría, with some short questions:

- Beef or rabbit stew? Lentil stew. I’m vegetarian.

- Mountains or beach? Mountains.

- Red or white wine? White.

- Music or silence when writing? SILENCE!

- What are you writing now? I haven’t started writing yet, but I have an idea for another historical novel about an Irish man most people never heard of, but who was influential in changing the course of Western literature.

Thank you so much, Anamaría, for such a open and informative answers about your process and characters.

Readers who want to know more – here is a selection of articles by / interviews with Anamaría Crowe Serrano:

- “Reconciling the Darkness”, for Books Ireland May 11.

- “Not all of them were fascists” for the Sunday Independent, July 4.

- Interview with Miriam O’Callaghan on her Sunday Show of July 4.

- Interview by Hilary A White in the Independent on Saturday 26 June

Connect with Anamaría Crowe Serrano via her website

Buy In The Dark from Turas Press

Thank you to Turas Press and Peter O’Connell Media for the advance copy of In The Dark