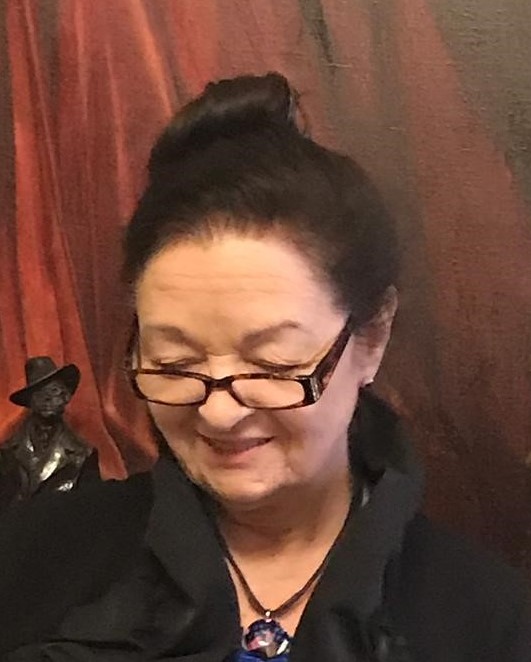

Celia, You’re very welcome to my Writers Chat series. We’re here to talk about Even Still (Arlen House, 2025) your debut short story collection in English which also includes “The Story of Elizabeth”, your short story shortlisted for Short Story of the Year Award at the An Post Irish Book Awards. The collection has been described as having “compelling” prose with “characters’ voices pitch perfect” and a “unique, characteristically stark, witty perspective on the lives of women and girls.”

SG: Even Still invites the reader into the emotional heart of each narrator – over a range of ages – and stays with some of them as they create life-paths out of places of poverty, away from damaged families and through schooling and employment that only echo where they’ve come from. Did these themed threads dictate the title and running order of the collection?

CdF: Thank you for the invitation, Shauna. I’m delighted to take part in the Writers Chat series. The word ‘debut’ seems strange applied to me at this stage of my life and so late in my literary career, but Even Still is indeed a debut collection of stories that were written on the side, over many years, while I worked in other genres. The title was chosen at the last minute, and with difficulty. I feel it suits the collection, however, as it suggests the possibility of alternatives. As for the running order, I thought it best to place the three stories that feature the character, Veronica, in chronological order. “My Sister Safija”, “Vive La Révolution” and “Irma” grouped themselves together. It seemed appropriate to place “La Cantatrice Muette” and “Félicité” between later stories, some of which have characters common to them. As you say, many of the stories explore the lives of characters who emerge from disadvantaged backgrounds, then attend schools / are employed by institutions in which they are challenged as a result of that background; the question as to how they manage to improve their lot is one that intrigues me, not only in this book, but in general.

SG: The collection is as much about place as people – starting with the cover art (‘Fitzwilliam Square’ by Pauline Bewick) – and the opening story “Pink Remembered Streets.” In these stories villages, towns, cities, and the buildings that form them rescue and trap their inhabitants. Can you comment on the importance of place in your stories?

CdF: The cover art, suggested by publisher, Alan Hayes, with its buildings, winding street and traffic, viewed by a woman from a height, is indeed appropriate. This is the first time I’ve been asked about place in my work and am happy to provide answers, insofar as they relate to this book. The buildings, in which the stories are set, are imagined, apart from the brief mention of a boarding school in “These Boots were Made for Me” and the houses described in “Pink Remembered Streets” and “The Accident”. Both of these houses were places in which I spent time; both were places of insecurity. The former is a flat in a house in Rathmines where I lived with my family during my early years, and from which we could have been evicted at a moment’s notice; the latter is my grandmother’s house in a seaside town in Northern Ireland where I spent my childhood summers, knowing the fun and happiness would end when summer drew to a close. Both houses have appeared in other work, as has security of tenure and the buying and selling of property. Another place that permeates the stories is the past, L.P. Hartley’s ‘another country’ where, in this case, there were few opportunities for girls and women.

SG: You tackle themes (such as domestic abuse, gun running, suicide, the poverty trap, cruelty) that could be weighty with, at times, a narrative voice that is wry and humorous. I’m thinking of the voices of Stella in “Panda Bears” and Eithne in “His Ice Creamio is the Bestio”. Was that a conscious, writerly decision or did those narrative voices emerge through the writing of the characters?

CdF: I tend to see the absurd in many situations and this is reflected in the stories “Panda Bears” and “His Ice Creamio is the Bestio”. In the former, Stella feels she must marry, not least on account of the urging of her friend, Eileen. The fact that both men she sleeps with wear hideous underwear and are poor lovers emerged naturally, as did the time in which the story is set: the opening occurs in late 1969, as suggested by the Mary Quant lipstick and the Beatles’ song; the fact that the timing of the gunrunning, set during the following Whit Weekend, coincides with the 1970 Arms Trial, was serendipitous. “His Ice Creamio is the Bestio” began life as a play in which I examined the lives of three generations of women from the same family, each of whom spent their formative years in different circumstances: grandmother, Eithne, from Northern Ireland, worked as a shorthand-typist during World War 11; her daughter, Francesca, an academic, grew up during the fifties in Dublin; Francesca’s daughter, Alannah, grew up in the Connemara Gaeltacht during the eighties. I found it bizarre, though credible, that three generations of one family could emerge from such different backgrounds on the same small island, and set out to explore how those differences impacted the characters.

SG: I’d love read a novel with these three generations! The stories often hold their power in the unsaid – or shown at a slant – whereby they rely on the readers’ close attention and intelligence to know or feel the real truth. Veronica’s stories, in particular, are great at this (the absence of Clara, for example). We know what happened to her – or we use what the narrative has stoked in our imagination. This makes it feel like these stories are a dialogue between writer/narrator and reader. Can you comment on this?

CdF: The subtlety probably spills over from my poetry where the number of words is more measured and the point never hammered home. I feel this approach works well in the Veronica stories, each of which focuses on the fate of a child: Clara, who falls prey to a paedophile in “Pink Remembered Streets”; the baby, Elizabeth, born of incest in “The Story of Elizabeth”; the unnamed boy, illegally adopted in “These Boots Were Made for Me”. I hadn’t planned that the common denominator in these stories would be the ‘child as victim’, as seen through the eyes of Veronica. Perhaps, because they are told at a slant, the stories demand the reader’s close attention, creating, as you say, an additional element to the usual dialogue between writer and reader; if this is the case, it was unintentional.

SG: And the unintentional is often the magic of the work! War, gender, and displacement are also explored in these stories, overtly in “Irma” and “My Sister Safija” which, as they’re bookmarked between other stories, seem to echo concepts of the outsider, whether it’s ideas of blow-ins, internal movement within the island of Ireland, or belonging through marriage. Did you set out to explore these themes or did they emerge through the stories?

CdF: War, gender, and displacement feature regularly in my poetry and it comes as no surprise that they have spilled over into Even Still. In addition, I should mention that some situations and characters in the collection are inspired by real events, though said situations and characters have been changed out of all recognition. The theme of the outsider, insofar as that person is from Northern Ireland, is one that worked its way into these stories. Having been born in the North and grown up in Dublin, I’ve always struggled to find out where I’m from, a question which drives much of my writing. I used to question whether I was entitled to explore my ‘Northerness’ as I hadn’t lived in the North during the Troubles but, more recently have come to better understand how the fallout from the conflict reaches beyond the Border. Though I didn’t set out to write stories populated by Northerners, these characters presented themselves and exerted their influence to varying degrees on the situations in which they became involved. As for belonging through marriage, Stella in “Panda Bears” is a young woman from Dublin who ends up marrying a Kerryman and moving to Tralee. This idea was also triggered by personal circumstances: I worked for some years in the Civil Service where the vast majority of colleagues were from the country and cast me, the Dubliner, as outsider – even though when I finished work and went home in the evening I was cast, alongside my family, as outsider because we were from the North.

SG: Much of your writing has the poet’s eye for detail, the dramatist’s narrative curve, and the prose writer’s depth. Your descriptions and visual take on lives also has the film maker’s sensibility. Could you see any of these stories as short films? (I’m thinking of “The Short of It”, for example).

CdF: It has already been suggested to me that some of the stories would work on screen. As soon as someone gets back to me with a firm proposal, I shall give it my serious consideration! “The Short of It” is the only story I set out to write as part of an agenda. Some years ago I was devastated when my work was plagiarised and exploited on a very public platform. One of my sons suggested I write a revenge story in the style of Michael Crichton: Crichton finds novel way to exact revenge on critic | The Independent | The Independent. Although my son’s suggestion triggered “The Short of It”, the story changed out of all recognition once I got going and now bears no resemblance to the travesty which gave it its initial impetus. I like the juxtaposition between the narrator’s circumstances when young, cash-strapped and working in the Civil Service, she adapts sewing patterns to recreate dresses featured on the catwalk, and her response, years later, when she realises her writing has been plagiarised.

SG: You are a bilingual writer. Were any of these stories first written in Irish, and, if so, how did you find the translation process in terms of idioms, flow, and narrative voice? If not, would you consider translating any of them into Irish?

CdF: “My Sister Safija” was originally written in Irish and is published as “Mo Dheirfiúr Maja” in Bláth na dTulach (Éabhlóid, 2021) an anthology of work by Northern writers. As such, I had to transpose it to Donegal Irish and needed editorial assistance. You can listen to it, beautifully read by Áine Ní Dhíoraí, here: Mo Dheirfiúr Maja le Celia de Fréine – Bláth na dTulach (podcast) | Listen Notes. I would consider translating any of the stories in Even Still into Irish for a film script or play.

SG: We will end this Writers Chat, Celia, with some fun questions:

- Bus or train? Tram. I love the LUAS. For longer journeys, I prefer the train but find myself travelling more by bus as bus stops are more accessible than railway stations.

- Marmalade or jam? Marmalade. Thick cut.

- Coffee or tea? An cupán tae, always.

- What are you reading now? When I’m writing I read little other than newspapers (at the weekend) and research / fact-checking articles. As well as the above, at present I’m dipping into There Lives a Young Girl in Me Who Will Not Die (Penguin UK, 2025) the selected poems of Danish writer, Tove Ditlevsen. Recently I read The Forgotten Girls: An American Story (Allen Lane, 2023) by Monica Potts; and You Could Make This Place Beautiful (Canongate, 2023) by Maggie Smith (not the actor). All three books explore themes covered in Even Still.

- These sound like great recommendations (I love Ditlevsen’s work!) What are you writing now? I’m about to sign off on the second edition of my poetry collection Aibítir Aoise : Alphabet of an Age (Arlen House, 2025); I’m also reworking my play Cóirín na dTonn with the team from An Taibhdhearc. Cóirín na dTonn was originally published as part of the collection Mná Dána (Arlen House, 2009 / 2019) and is recommended as an optional text on the Leaving Certificate Syllabus. I also have two projects on Louise Gavan Duffy, inspired by my biography Ceannródaí (LeabhairCOMHAR, 2018), on the back burner. As all these projects are based on, or inspired by, earlier work, I long to clear space for new poems, and get back to a YA novel in Irish which I began a couple of months ago.

Thank you, Celia, for such insight into your writing life and process. Here’s to finding clear space over the coming months and continued success with Even Still which can be purchased in Books Upstairs.