Eamon, You are very welcome to my WRITERS CHAT series. Congratulations on Dolly Considine’s Hotel which was published by Unbound in 2021. I must thank you for taking the time to do a reading as part of this WRITERS CHAT – readers, you’ll find the reading mid-way through this chat so treat it like an interval!

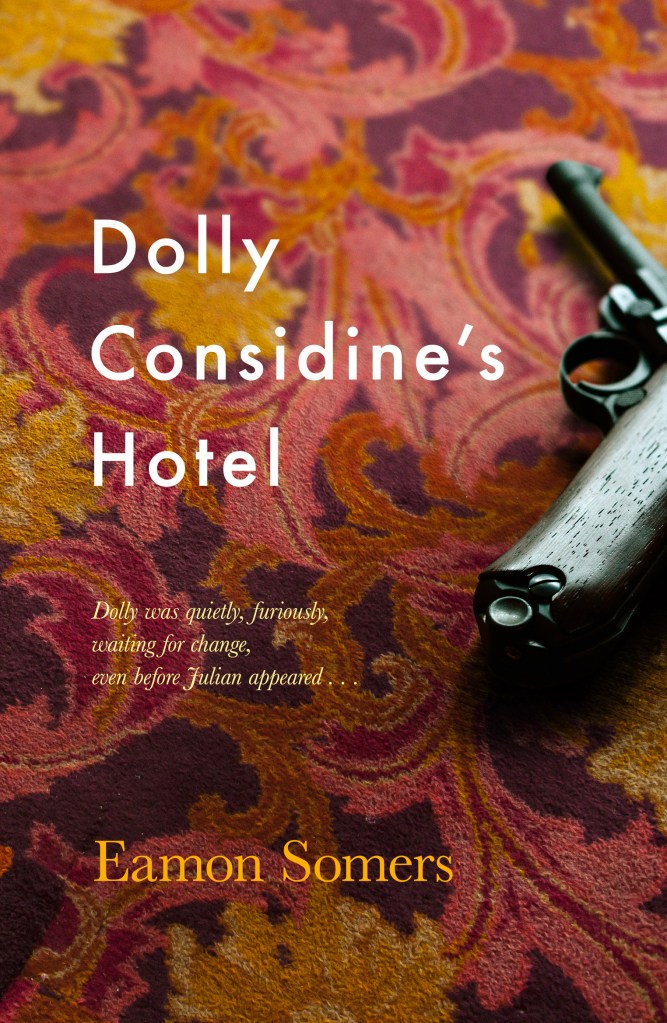

SG: Before we get into the details of the characters, history, politics and love in Dolly Considine’s Hotel, I was struck by the honesty with which you describe the writing journey and path to publication. I think it’s very refreshing. Can you talk a little about this and your experience with Unbound and may I, in the same breath, comment on the perfect cover. I just love that patterned carpet and the revolver. It captures so much of what the novel is about.

ES: Hi Shauna, it’s an absolute pleasure and a privilege to be invited onto your famous writers chat. Let me start with the cover which was designed by book designers Mecob and has received a lot of praise. I tracked down the patterned carpet photo on Shutterstock, it was taken by Irish photographer Julie A Lynch and she called it “creepy old hotel in ireland carpet”. If anyone knows Julie, please pass on my gratitude to her for such a great image.

I submitted an earlier novel to over 100 agents and publishers. One agent was interested, and we worked for months to get it ready to send out. But without success. He told me to put that novel in my bottom drawer and to write another. I resurrected something I had previously worked on, and Dolly was born. But by the time I had an acceptable draft, the agent had moved on, and I started the submission business again. Eventually, just as I was about to give up and self-publish, Unbound said ”yes”.

Unbound operates like a traditional publisher, except that their financial model requires publication costs to be raised through a crowdfunding campaign, run by the author on the Unbound website. That was hard work, but very rewarding especially because it introduced me to the world of promotion via social media. With so many books being published it appears that unknown and debut novelists have little chance of finding readers (and as, importantly, reviews) unless they embrace the world of Twitter and Instagram.

SG: Yes, these days as well as writing the novel writers are expected to promote their work across multiple social media platforms – hard work when you need to be writing! But now let’s talk about the structure of Dolly Considine’s Hotel. There’s a split timeline for most of the book – between 1950s and 1980s – and it’s through the two stories, running along almost like parallel tracks that we come to understand the significance of the Dolly’s hotel as the main character. Coupled with the wonderful chapter titles (for example, “No Time To Be Squeamish”, “Julian Remembers the smell of chocolate that encircled the Cadbury girls”, “A visit to the theatre”) and the short, snappy chapters, the novel is a surprisingly fast read at over 500 pages. Did the structure play as important a part in writing as it does in the reading experience?

ES: I didn’t start out to write anything complex. I wanted to set the story in a version of an hotel I had briefly worked in when I was in my early twenties. And because I was very disillusioned with Ireland after the pro-life referendum was passed and the possibility of divorce was rejected, I wanted to portray life in the early ‘80s. I admit to wanting to write something a bit different from the usual linear story: hero/heroine overcoming obstacles to find themselves or love. More importantly I wanted to play with readers, to upset their trust a little, hint at unspoken complexities, cast doubt on the certainties they expected, give them shaky ground, like a fairground ride. At the time of writing, experimental writers were beginning to play with multimedia things and to give readers some power to control the story. But that wasn’t for me, instead I tried to give entertaining variety from which readers could choose what to believe and what to just laugh at. This may not answer your question, but the hotel building has been around for two hundred years, and I wanted to share the histories that made it the complex entity that it is today. History doesn’t happen overnight; it is built up and built upon over many years. Ghosts have to come from somewhere. And Dolly has lived/is living through periods. She chose her path (or it chose her) in the ‘50s, when she moved into the hotel, taking with her own family’s history.

SG: I found there was a lot to laugh, disbelieve, and wonder… but alongside this playing with the reader, one of the main themes is that of identity and gender; the names we call each other, the names we call ourselves, the limitations and expectations of society and of ourselves. Dolly’s hotel is a type of refuge for those who want to step outside the norms of 1950s/1980s Ireland. And of course, Dolly Considine – and through the hotel – plays with notions of power and politics, from her seduction of GI and Cathal, to her hold over the staff. Can you talk about Dolly, identity and gender?

ES: Identity is very important to me. I was married at 22 and was the father of two children by the time I found out/acknowledged I was gay and my marriage broke up. Often when I meet new people it is the fact that I have children that emerges rather than the fact that for nearly forty years I have lived in a committed relationship with another man. So (as a committed zealot) I feel obliged to correct any assumptions. Less frequently, but equally, I feel obliged not to deny my children when I make new gay friends. This is who I am, as is my Irishness, and my confused class heritage.

If Dolly or other characters defy expectations, then I am pleased. The female characters perhaps try to control their environments, but I think they have to reduce their expectations, so they are in line with what is possible. And although it was Julian that was the inspiration, I had wanted more for Dolly than she got. So, in that sense I let her down and allowed the lion’s share of attention go to the male protagonist.

SG: And to be honest that is probably why I picked her out for that question! I wanted more for her too!

I loved how the meta-narrative of the novel that Julian is writing – “The Summer of Unrequited Love” – evolves with the main narrative (that of the hotel) in such a way that we have trouble distinguishing between the action in Julian’s notebooks and those in the hotel, just as Julian himself does. At one stage, “It had only been seven or eight hours, but his fingers were twitching as if they’d never hold a pen again.” And, for example, we’re in a scene in which Julian’s lover, Bláthín, has had most of the wine:

‘The wine was gone. She’d had the most of it.’ He whispered the words to fix them in his head. It would be a springboard line for his journal. He leaned into the low table to search for blank paper she wouldn’t miss; even his own mother kept scraps for shopping lists. His pen already in his hand, twisting like a divining rod tuned to blank paper.

How important to you were these parallel stories which reflect and talk to each other to what you wanted to say through the novel about the acts of perceiving, recording, and writing?

ES: The parallel stories confront the reader with a messy, erotic, unashamed version of Ireland. In the extract you choose, Julian is writing his fictional Summer of Unrequited Love, while also participating in the real-life events of Dolly Considine’s Hotel.

Julian is a young idealist, and a “real” artist, ready to “suffer” for his art. But equally there is the serious work of how a writer portrays their characters. Which aspects of their behaviour will best represent them? Julian wants only meaningful characteristics, the ones (perhaps just one) that will resonate instantly with his readers; he wants to ignore those that merely pad out the portrait.

But Josie’s story, Sylvia’s story, Dolly’s father’s story, Brendan’s story all explore, and as you say, talk to the main and ostensibly more reliable/truthful narrative, and hopefully in their own way, produce a more meaningful truth and deeper feelings in the mind of the reader.

Eamon reads two short extracts featuring Dolly and Julian

(total time: 4 mins, 10 seconds)

SG: Thank you for such a wonderful reading, Eamon. So, following on from that reading, we can say that much of Dolly Considine’s Hotel examines bodies and terminations – ideological, political, literary – through acting and enacting, writing and reading, interpreting and imagining. It’s a slow build – starting with Mikhail Mayakovsky/ the Mother Ireland scene and returning to it later – and continuing with the series of “Terminations” in Julian’s notebook – whilst following the adventures of Julian’s body in the hotel and beyond. I also couldn’t help feeling that the side exploration of urban/rural – for example, when Bláthín tells Julian in Cavan to “listen to the babies…you can’t come down here and trample anywhere you like. You have to respect the established order.” – also echoed this theme of bodies. I thought it was an interesting way to explore choice. Can you comment on this?

ES: Although it is not foregrounded except perhaps in Cathal’s naming, and Julian’s frustration at not understanding the history of the state’s inception, I was conscious of the civil war all the time I was writing the book. As a nationalism sceptic I don’t want to big up too much the “idealism” of 1916 and the war of independence, but for me the civil war marked the termination of those aspirations embodied in the Irish Literary Renaissance of the 19th century, and which were then fetishised and mythologised in the new state. Mother Ireland and her pregnancy reminds us of the loss of idealism and choice that the pro-life victory represents. Many of us who grew up in cities (but especially Dublin) under Eamonn De Valera and Bishop John Charles McQuaid were made to feel that the authentic Irish lived in the country. Dubliners are Jackeens, they took the king’s shilling, they were not to be trusted. Bláthín has absorbed the myths and is retelling them in her radio work, but she also recognises that Julian might have his own working class inner-city naive truth.

SG: Yes, of course, there’s the theme and voice of class running through the novel too. Now, we’ve discussed some of the themes and narratives but I can’t leave this Writers Chat without mentioning the humour and the chance encounter (or was it a chance!?) between Paddy/ Julian and the mysterious Malone in Busárus that sets Julian on the road to Dolly’s hotel. You really capture that era (1983), one in which the world outside Ireland was full of possibilities but an Ireland which was closed in on itself in every way (economically, sexually and so on). Can you talk about the genesis of this beginning?

ES: The people of Ireland’s 26 counties often get criticised for ignoring and/or completely misunderstanding what life is like for people who live in the North of Ireland. I wanted to play with the complexities and to allow Julian to have what he considered to be reasonable (but were often conspiratorial) interpretations for the things he witnessed/imagined about Malone, and about Dolly and GI – viz the safe house. But I also wanted a cross border romantic interest, even if the erotic only went as far as Julian wearing Malone’s pants and underwear.

SG: And speaking of pants and underwear, the erotic – particularly, male – is key to the novel and yet is not the only theme that defines it. How would you categorise Dolly Considine’s Hotel – if it can be categorised or boxed?

ES: I think of Dolly Considine’s Hotel as a post-gay novel, a book where the issue of sexuality is taken for granted. This doesn’t make characters nicer or less nice or even more worked out, but their sexuality is just a fact, like their eye colour. Recent years have seen a market opening up for gay fiction across all genres, however in my writing I seem to have been regarded as either too gay for mainstream publishers or not gay enough for niche publishers. And although it was not my intention when writing the book, I’d love to think that Dolly can bridge that divide.

SG: To finish up, Eamon, some fun questions

- Countryside or city? Except for three months when I was eleven (on a Gael Linn scholarship in Connemara) I have always lived in cities. Like many city dwellers I secretly think I would love the countryside, but in reality, suspect I will always prefer to visit rather than live there.

- Tea or Coffee? I am definitely a coffee person. But have very little time for fussy machinery, or coffee shops, and except for weekends, will settle for instant. I switch to decaf at noon.

- Bus or train? I love trains, especially for long journeys. But in the city I like buses, so much better for linking London’s villages. And during covid, somehow safer than the underground.

- First draft handwritten or typed? Typed, onto my old Amstrad in 1998, although I was also very fond of a notebook, but mainly for late night drunken ramblings.

- What’s next on your reading pile? I supported my fellow Unbound author Patrick McCabe’s crowdfunding campaign for his latest book, Poguemathone and I’m looking forward to getting stuck into that.

With thanks to Eamon Somers and Unbound for the copy of Dolly Considine’s Hotel – purchase the book here