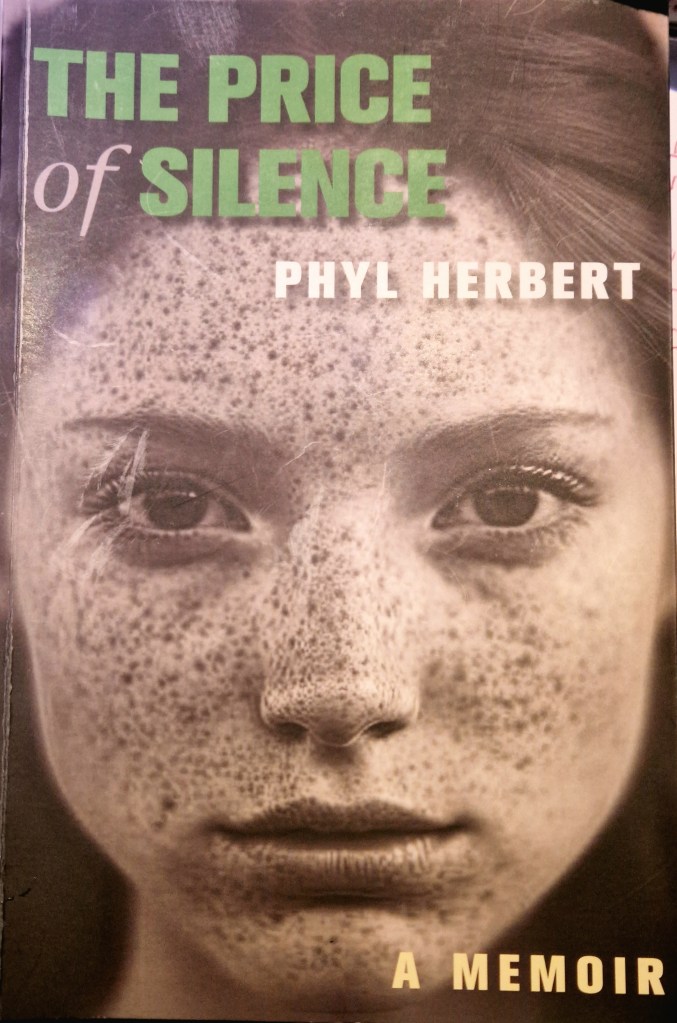

Phyl, You are very welcome to my Writers Chat series. We’re here to discuss The Price of Silence, A Memoir published in 2023 by Memna Books, Cork and launched, in Danner Hall, Unitarian Church in Stephen’s Green, Dublin in November to a packed room. Congratulations!

SG: Let’s begin with the title which tells us something perhaps about one of the themes of this memoir, and of your life, The Price of Silence. Can you talk about how you came to decide on this title?

PH: After searching through a number of titles, I knew that the motif of Silence was embedded in the storyline ranging from the young girl losing her tongue in the beginning of the book to the fact that there was a total lack of vocabulary to talk about the abuses she experienced. Such experiences had no words then. The final experience of becoming pregnant by a married man which in itself was not a topic for discussion but in l960’s Ireland to become pregnant outside of marriage was not only socially unacceptable but the pregnant woman was treated as a pariah and an outcast. So Silence was the defence mode of existence.

SG: The Price of Silence speaks eloquently, not just of your own existence, or story, but of what it was like to be a woman in Ireland during these years – the late ‘50s. ‘60s ad beyond – and, in particular, how the body, desires, ambition were silenced and controlled, and how language was used to silence and name. Were you conscious of the power of social history when writing your own story – in other words, aren’t we all formed by place and time?

PH: Yes, I was conscious of the power of social history and that is more or less why I wrote the memoir. I wanted to write myself into existence and by so doing attempt to analyse those decades that I lived through. Men ruled the institutions, and the voices of women had not as yet emerged, but there was the beginning of movements such as The Womens’ Liberation Movement that were creating platforms where women could express their grievances. But there was a long way to go.

SG: The Price of Silence is divided into four sections, and the opening section “Tree Rings” brings us through your childhood by way of sharp memories, many of them sensory, that seem to relate to you as a creative person – writer, actor, teacher – and very much in touch with your surrounds. Can you talk about the importance of where you grew up – that pull between Dublin and Wexford?

PH: The pull between Dublin and Wexford was deeply felt. It represented also the pull between my mother and father. My mother never liked Dublin or the house where she reared her family of eleven children. But she never rebelled, she never expressed her desires because then a woman didn’t know how to talk about such things. I felt her lack of expression at a deep level and I think I was always conscious of the need to develop my own language, my own identity. I was a dreamer at that young age and sought means for escape. Drama and the imagination helped me though. I wanted to be able to express in words what I felt. To put a name on a feeling, on a thought.

SG: That deep need to express feeling and thought comes through very clearly in this memoir. Alongside your creative outlets, your teaching career took you around the city of Dublin in secondary education, further education, and prison education with the common thread of your approach to education as what we might call a Freirean approach (echoing Brazilian educator Paulo Freire’s belief that educators need to meet people where they are at, rather than the “banking” method of education whereby teachers “feed” information to students and they regurgitate it back again). Do you think this linked in with your approaches to acting and drama and the importance of those in your own life?

PH: Yes, I believe that our whole lives are about ‘Negotiating into Meaning’ a phrase used by Dorothy Heathcote, Newcastle Upon Tyne University where I studied for an M.Ed. In Drama in Education. Her philosophy was to provide a mantle enabling the child to find his/her voice. In the Stanislavski Method of acting, the truth of the character was plumbed into the depths of your own existence, your own humanity.

SG: What pulses and aches right through The Price of Silence is your experience with pregnancy, birth, and motherhood. This is your memoir – not that of the man with whom you had a daughter, and nor that of your daughter – but they are both there, with you, even in their absences. Was it a difficult process ensuring that The Price of Silence told your story only?

PH: What a great question. Yes, it was difficult because I had to protect the identity of my daughter. She has her own story and that is not mine to tell. I still didn’t manage to achieve that in that there were times that her voice was necessary to present the story. The birth father is deceased but his children live on. I’m sure I’ve made some mistakes here also but of course I didn’t reveal their identity.

SG: Lastly, Phyl, the pacing and storytelling of The Price of Silence coupled with how the memoir is structured added such an emotional push to the book that I read it in one enthralled sitting. What advice would you give to those hoping to write their own memoir?

PH: Everybody is different. People say to be truthful. But there is a high-wire balance to be achieved. It’s not good to be too truthful, there has to be a distancing perspective but at the same time I think an immediacy has to be achieved. E.G. I wrote some of my memoir in the present tense. Ivy Bannister says, ‘Think of your life as a train journey, what station will you get on and what is your destination.’ That sort of worked for me.

That’s a great piece of advice from Ivy and yourself. Lastly, Phyl, some short questions:

- Quiet or noise when you’re writing? Quiet. Or quiet music in background.

- Mountains or sea? Both. I spent some time in The Tyrone Guthrie Centre. Bliss.

- Coffee or Tea? Coffee. But not many cups.

- What’s the next three books on your reading pile? Just finished Christine Dwyer Hickey’s ‘The Narrow Land.’ Superb. ‘The Strange Case of the Pale Boy and other mysteries.’ by Susan Knight. ‘In the Foul Rag-And-Bone Shop’ by Jack Harte. ‘The Deep End’ A memoir. By Mary Rose Callaghan.

- A great reading list, thank you! What’s next for your writing? A One woman stage show about a nun who leaves the convent before her 50th birthday and discovers Tango Dancing as a way into unlocking her repressed emotional life.

That sounds intriguing, Phyl, I very much look forward to it. Thank you for your generous engagement with my questions and I wish you every continued success with The Price of Silence.

Purchase The Price of Silence from Menma Books or from Books Upstairs, D’Olier Street and Alan Hanna’s in Rathmines, Charlie Byrne’s in Galway.

Phyl Herbert, Mary Rose Callaghan and Liz McManus will feature in Books Upstairs in an interview about memoir writing on Sunday afternoon 28th January, 2024.