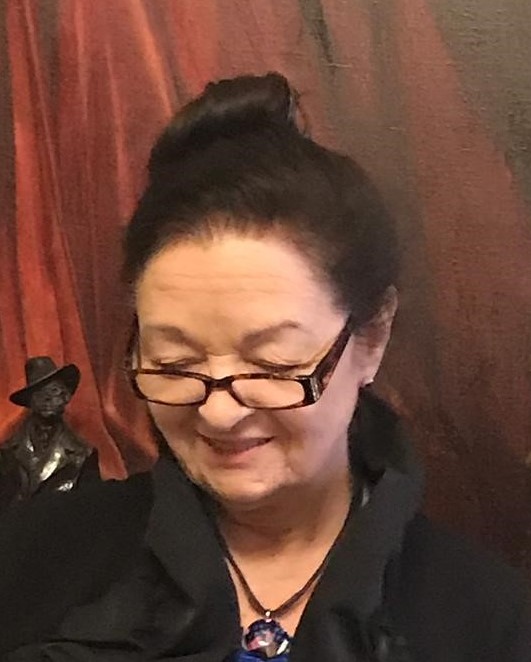

Mary, you are very welcome to my Writers Chat series. We’re here to discuss your short story collection Walking Ghosts, a collection which has been described by William Wall as “fascinating, and utterly compelling”.

SG: I love the title, the fact that the ghosts are walking and how this connects to the importance of time in the collection. Many of these stories were published in journals and magazines nationally and internationally prior to their inclusion in this collection. Can you talk about how you compiled the collection – the order of and the naming of the 17 stories, and perhaps stories you might have left out?

MOD: Hi Shauna, great to be part of Writers Chat! The question of how a story collection comes together depends on the writer. For me, the stories are usually set down quite slowly, and I notice that in three of my short story collections there has been a ten year gap between each one. This is probably because I’m also a poet and novelist, which means I have other projects underway, or I’m thinking about them. When a short story seems urgent to me, I’ll set it down and get an early draft underway, before ‘parking’ it for a while in order to let the basic thrust of it to settle. Then, later, I’ll return and scrutinise what I’ve written and see if that’s true to what I intended. Anything can happen at that point.

SG: That sounds like good advice, Mary, thank you! Now the opening story “Cocoa L’Orange”, gives us a poignant yet humorous picture of a relationship whose troubles are revealed during lockdown.

Sasha, “considers reading to be a positive thing. Jake has never bothered with fiction, preferring non-fiction and biographies”

This sets the scene for an examination of identity, meaning, usefulness, and productivity in society and between people. How did this story come to you? During lockdown or afterwards?

MOD: It came to me in the final year of lockdown. I was very struck by how awful it may have been for some people, and how isolation enhanced difference or even great difference for some people, while others paddled along and were able to get through. In the case of Jake and Sasha, I imagine them actually getting through this together despite frictions, but the point is that his sense of masculinity has been undermined by the collapse of his business, to the point where he is emotional frozen. The only outlet that approaches a thaw is contained in the moments when he and his equally failed male neighbour gaze across the gap between their houses, from window to window, in a silent acknowledgement of some kind. I think if I were Jake I’d probably poison Sasha—the story is told from his point of view, not hers—because she is pragmatic and a little unsympathetic to his plight.

SG: Yes! Your use of silence was so powerful in that story. In many of the stories you bring us into the inner world of the protagonist allowing us to experience their world view. I thought this came through wonderfully in the moving “Edna” with the pitch perfect pace and tone which made me feel I was with Edna both in thought and in movement. Edna has “thoughts like a slow tide” as she moves slowly through a Dublin where she feels she is still not a “fully fledged” city person. She dispenses hugs and fivers to alleviate the deep well of missing her daughter who is pregnant and abroad and tries to make sense of people through snatches of conversation. In contrast, Roberta in “Like Queens not Criminals” moves through London, a city she is not familiar with, and tells herself as much as us that

“I do know something about beauty, how it lies in wait at the dark heart of our lives.”

Similar to “Edna”, “Like Queens not Criminals” is an exploration of loss and identity and finding solace in ordinary places. Both stories also serve as quiet critiques of how Ireland views the marginalised and bodily autonomy. Did these themes emerge through the characterisation or did you have them in the back of your mind as you wrote?

MOD: That’s a really interesting comparison Shauna, one I hadn’t thought of. The theme of how we move through space interests me, and in ‘Edna’ I did want to place an older woman out in the city, someone whose sense of autonomy is quite strong, and who believes in helping others in unconventional ways. She is not a do-gooder trying to feed her ego, but nor is she quite prepared for what happens when she unintentionally breaks the body space of someone who is vulnerable. There is a beauty to both cities for each protagonist. In ‘Like Queens not Criminals’, Roberta is in London in the early 1990s for the purpose of having an abortion, so she views the city through highly self-aware eyes on the days she is there. She has abandoned her own country to do this. She has made a decision to do what she believes is best, just as Edna some twenty years later decides to do what she believes best but in her home city.

SG: There is much humour in this collection, too. “The Space between Louis and Me” had me laughing out loud; “The Stolen Man” had me smiling with recognition; “The Creators” had me nodding in agreement. Humour is, to use Dickenson’s phrase, a slant approach to more serious themes or topics that are explored in these stories yet there is a lightness of touch here too that makes me wonder if it came from the actual writing. Did you have fun writing these three stories in particular?

MOD: I find it difficult to keep my own sense of humour—sometimes ironic, sometimes satirical, and yet other times downright mocking—out of the narrative. This is probably because I’m an unreconstructed free thinker who is never more happy than when she discovers conventional boats being rocked. I do enjoy it when my characters take situations into their own sometimes inept or intolerant hands, because their intentions are good behind it all!

SG: I love that “inept or intolerant hands”! Finally, if there is an overarching theme to this collection it is how identity is fluid and formed and re-formed with and by those we meet – both intended and chance encounters – and where we are in the world we are – travel for all its reasons. I’m thinking here of “Luck” and “Peace, Love and Pushpanna” and the power of conversation. Can you comment on this?

MOD: We are constantly being pushed, nudged and prodded by our experience and by our encounters with others. In ‘Peace, Love & Pushpanna’ I took a newly married young woman in the late 1970s and her rather pedantic husband and situated them on a break with relatives in London. The cultural encounter—without giving anything away—is what is going to change her and (it is my hope if this were ‘real’) make her leave him. I hate boring people, or people who are boring to me, and I just had to suggest that there are better, happier ways for this fun young woman to live! In ‘Luck’, the central character, a tarot-card reader is himself extremely lucky on the day—a complete chancer, a man of weak character with betrayal in his background, he has somehow managed to turn his own fortunes around and has landed on his feet!

We will end this chat, Mary, with some short questions:

- Bus or train? Train!

- Coffee or tea? Coffee.

- Quiet or noise when you’re writing? Quiet-ish with people sounds from outside is best. Ideally, a library, but the last time that happened I was on holiday in Mallorca and the hotel had a small library with a balcony overlooking the reception area, so I was away from everything, yet part of a slight buzz of activity, and I was revising by hand the story ‘Edna’!

- Your favourite story that didn’t make it into Walking Ghosts? ‘Native’, a story which will be the title story of the Spanish translation of a different collection of stories, due out in January 2026. In ‘Nómadas’, as they’ve called it, a commercial watercolour artist and her daughter become drawn, even fascinated by a family of Travellers on the road they live on.

- What are you reading now? ‘Big Kiss, Bye-Bye’ by Claire-Louise Bennett (Fitzcarraldo Editions)

Thank you, Mary, for participating in my Writers Chat Series and for your thoughtful answers to my probing questions! Walking Ghosts can be purchased directly from Mercier Press or from your local independent bookshop.